- Tower of London

- Torture and punishment

The man who captured the tower

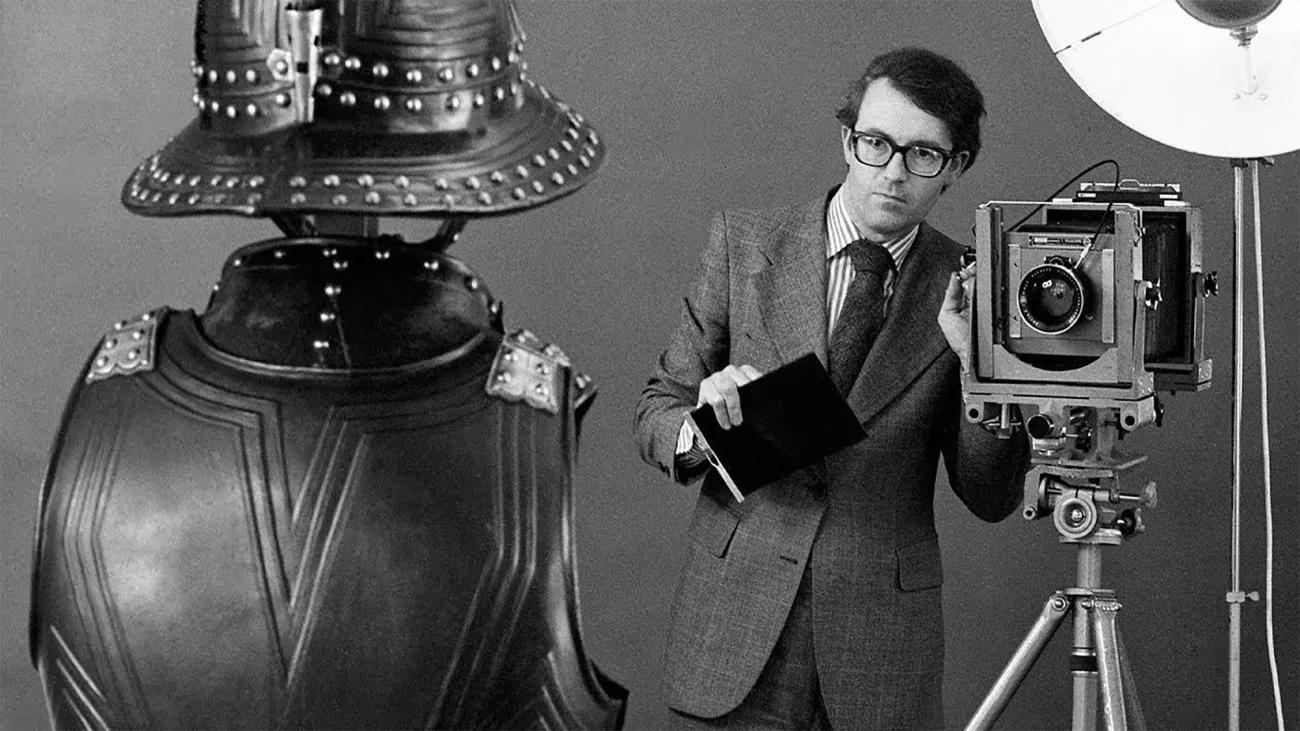

Jeremy Hall was Photographer for the Tower of London from 1967 to 1996. This period was marked by significant change, both for the institution and British society. The Tower’s Armouries Museum left direct control of the Civil Service and began to adopt a more modern approach to presenting history. At the same time, British culture was being shaped by an accelerating public appetite for both taking and consuming images.

Jeremy’s role at the Tower also evolved. As time went on, he started to take the kind of promotional images that became a default element of modern marketing. But Jeremy always stayed true to what he saw as his core duty, which was creating a meticulous record of the Tower’s buildings and events, and the Armouries’ collections. What can his photographs tell us – not only about the man and his work but also the unique institution he took great pride in serving?

10 minute read

Access all areas

Jeremy was originally seconded from a job as a photographer for the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works, only gaining an official position at the Tower in 1983. Much-valued by colleagues, he was meticulous, knowledgeable and kind. Adhering to Civil Service dress codes of the time, he was also almost never without a tie. Jeremy’s primary role was to take pictures of the site’s buildings, archaeological digs and formal ceremonies, as well as to create a photographic record of the Armouries’ collections of arms and armour. He also took formal portraits of Yeoman Warders and other Tower personnel, and captured everyday moments in the life of what remains one of the world’s most famous buildings.

The Body of Yeoman Warders or Waiters of The Tower of London were established to guard the site and any resident royal prisoners. Exactly when is lost in the mists of time but it was likely to be in the 1200s. The instantly recognisable full-dress uniform which we still see today, arrived in the 1550s, courtesy of a former inmate at The Tower itself. Edward Seymour, 1st Duke of Somerset and uncle to the teenage King Edward VI, had scaled the greasy pole of Tudor politics to become Lord Protector of England by 1547, but had found himself imprisoned two years later. When he was released and restored into the King's ruling the following year, he petitioned his nephew to reward his jailers for taking good care of him. They were appointed Extraordinary Yeoman of the Guard - a title and role they still hold.

This unique body of guards first accepted women in 2007, and currently includes 32 personnel. A minimum of 22 years’ military service with honours is a requirement of the job – as is a loud voice, an outgoing personality, and a friendly attitude in the face of constant selfie requests.

Building a legacy

Jeremy was art school-educated and, before entering the Civil Service, worked as a graduate assistant to an architectural photographer. These formative experiences primed him for taking creative pictures of buildings. Spanning many centuries of English architectural style, the 18-acre Tower of London site was the perfect place to develop his craft. Over time, Jeremy shot lots of images of the White Tower, which remains one of the world’s most famous fortified buildings. When he started work in the late 1960s, The Tower had already developed its iconic status through the growth of tourism and the golden age of postcards dating back to the 1890s. Jeremy's careful use of the distilling power of black and white meant many of his images now stand as far more than just a record of their subjects.

In July 1974, a large bomb was detonated under a cannon in the basement of the White Tower Although no group ever claimed responsibility, the attack was widely believed to be part of a bombing campaign mounted by the IRA in the UK that year. Whoever planted it, the choice of location was no doubt linked to the Tower’s important role in Britain’s national story. The bomb left one visitor dead and 41 people – including many children – injured, some severely. Tower staff worked into the following winter with their office windows kept open, to protect them against shattering glass in the event of a repeat atrocity.

Overground, underground

From time to time, Jeremy was called into the grounds of the Tower to take pictures of an archaeological dig – and according to colleagues, whatever the weather, always without a coat on. This kind of work would have been familiar to him from his previous role, as a photographer of ancient monuments. The evidence of previous eras that these digs uncovered, acted as a reminder that the site’s human history stretched back further even than the building of the Tower’s Norman keep.

In 1937, workmen digging in the grounds in an area that used to be under the waters of a moat came across the skulls of two lions – the oldest of which was dated to around the end of the 13th century. Both were found to be specimens of the Barbary lion. This subspecies is known for being used by the Romans to battle gladiators at the Colosseum, and has been extinct in the wild since 1922. The skulls were evidence of the long history of the Tower’s royal menagerie, a collection of exotic animals that was kept onsite until 1835.

An eye for detail

Not all of Jeremy’s architectural work focused on the more iconic aspects of the Tower site – he also carefully documented the way its buildings were maintained or adapted by programmes categorised as ‘Major Works’. Doing so often helped underline how some of London’s most famous buildings had evolved over time. An example is a functional picture of an unexciting new external staircase at the White Tower in 1974: a useful reminder of the fact that the original Norman entrance was well above ground level. (This arrangement meant that in the event of an attack, the wooden staircase could be hacked away at speed, helping ensure the safety of the people inside.)

In 1996, much of the Armouries’ collection moved up to the museum’s brand-new building in Leeds. This meant that the White Tower had to be extensively reorganised. On its top floor, the removal of wall-mounted display cases revealed the sooty triangular outline of the original Norman roofline. This trace was clear evidence of how Henry VII had raised the roof in the 1490s to create extra space for stockpiling gunpowder - something that was then cutting-edge technology. This new substance fuelled the muskets and cannons that would soon make extensive body armour (and Medieval-style warfare in general) redundant.

The right facilities

Jeremy’s most consistent task during his time at the Tower was creating a visual catalogue of the Armouries’ extensive collections. This meant patiently working his way through thousands of individual items of arms and armour. When his dedicated studio was still in the Flint Tower (part of the site’s inner defensive wall), staff had to bump items up three flights of spiral staircase, including suits of armour wrapped in layers of protective rags. In the 1980s, Jeremy’s dedication was rewarded with a new, purpose-built studio and darkroom in the main museum building. This new space came complete with a special toilet. One of Jeremy’s colleagues had worked hard to find one with a flush mechanism that didn’t produce excessive vibrations – lorries rumbling along Tower Hill had sometimes created focus problems for Jeremy’s plate camera when he was in the old studio.

Ensuring images perfectly reproduced the texture, tone and decoration of metallic objects to create an accurate archive was a significant technical challenge. To achieve the best results, Jeremy had to use a large-format camera – its huge photographic plates could capture a lot more detail than standard 35mm film. Although digital technology has made analogue plate cameras a niche choice even for professionals, it’s this kind of vintage camera that is (complete with signature concertina bellows) still used on the road signs that warn drivers about speed cameras.

Floor puzzle pictures

An in-house photographer was useful to the Armouries’ curatorial staff when they were planning the layout of exhibitions. Collection objects would be laid out on the floor on a grid plan, and Jeremy would make reference shots of each item. He then made quick prints that the curators could pin up in display cases, allowing them to try out or compare different configurations without having to keep moving heavy or delicate objects. Jeremy also worked closely with curatorial staff on shooting particular archival images – he apparently made huge efforts to dull down or highlight particular details.

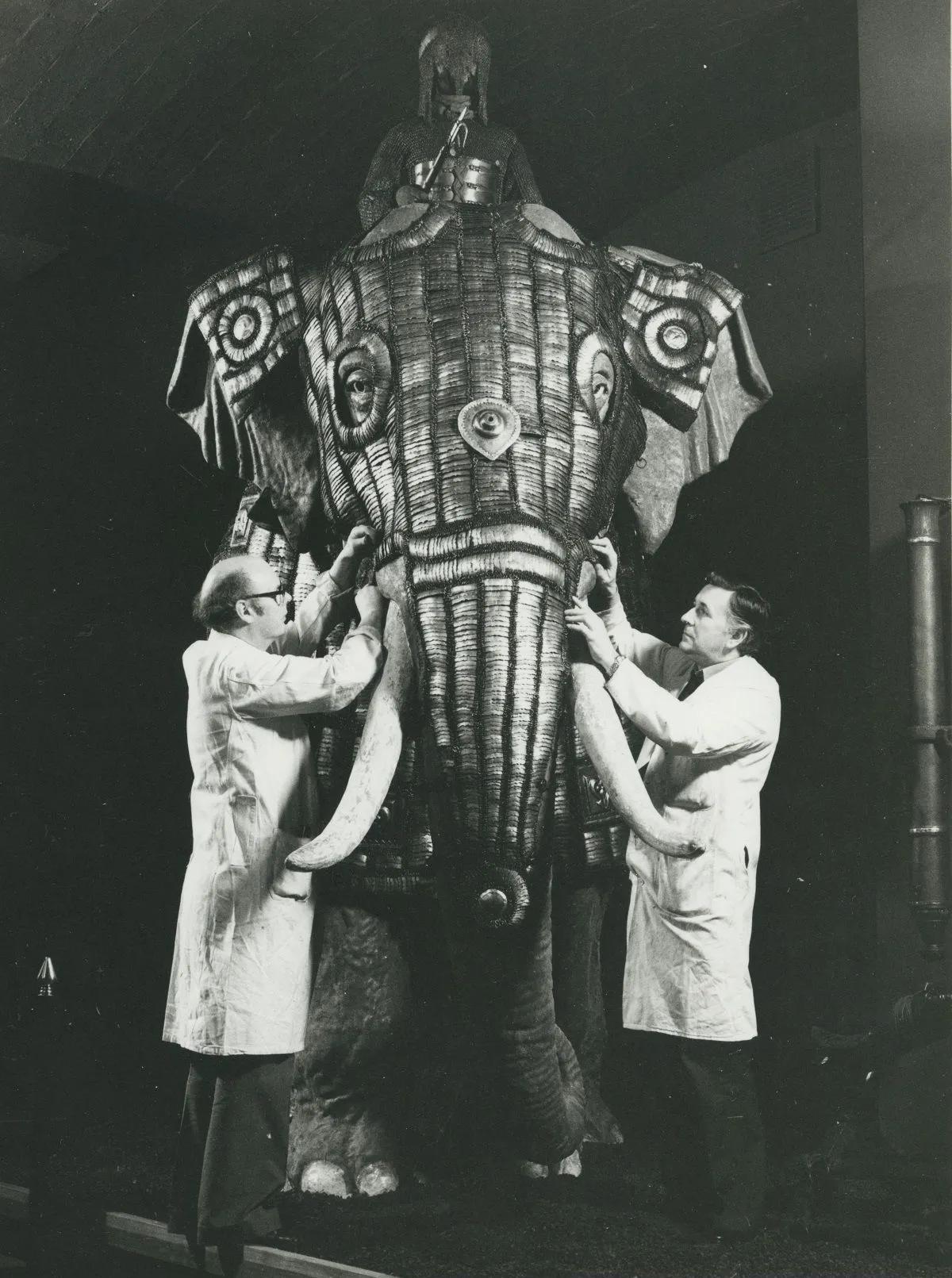

Although gunpowder caused the widespread use of battle elephants in Europe to die out by the 15th century, they continued to be part of standing armies in Asia. The Armouries’ Elephant Armour – an incredibly rare piece made in India in the 17th or 18th century – is one of the most popular items in its collection. In 1976, it was newly displayed on a fibreglass elephant – an upgrade on the previous wickerwork version, which used to be slept in by the museum cat.

The well-guarded myth

Taking pictures of official ceremonies at the Tower of London was an important part of Jeremy’s remit. Some of these events featured royal guests – so he and other Tower staff were encouraged to always come to work ‘dressed suitably to meet the Queen’, just in case. (Women working at the Tower were barred from wearing trousers into the early 1980s.) As time went on, Jeremy began to widen his interest in public symbols of the Tower, in particular the Yeoman Warders. Always impeccably polite, Jeremy always made sure to ask the permission of their commander, the Chief Yeoman Warder – an imposing figure who played a highly visible role in both everyday routines and big events.

As tourism expanded, people began to take more interest in the Tower’s ravens. Although the birds are now inextricably linked with the Tower, their presence there was not made a focus in guidebooks until about the 1950s. Ravens would have lost their London roosts as a result of growing urbanisation in the 19th century. So it’s probably the Victorians – maybe driven by nostalgia – who are responsible for encouraging the gothic story that says these striking birds are crucial to the Tower remaining upright.

A key part of promotion

Although Jeremy took great care over all the images he produced, many of them were only ever seen by Tower staff. But the 1980s ushered in a new era of consumerism and more choice in forms of leisure. As a result, demand grew for him to produce commercial work to encourage people to come and spend their money at the Tower. Jeremy began to take pictures of the more famous objects in the collection for postcards, books and posters. Although he continued to prefer to work in black and white, modern taste demanded he shot a lot of this promotional work in colour.

Henry VIII’s four suits of armour are still among the most popular items in the Armouries’ collection. Together they chart his progress from a young, fit man to one who had developed a sizeable belly and crippling gout. For a modern audience, in all these suits of armour, the Tudor codpiece is often a focal point for comment. Victorian curators at the Tower removed any risk of visitors making inappropriate jokes by mounting their older Henry VIII on a horse – meaning his codpiece was taken off. And for the display of his suit of foot combat armour, they presented Henry with hands at groin height, holding a broadsword with a generously sized hilt.

Within these walls

Jeremy genuinely enjoyed taking pictures and didn’t see the end of the office hours as a reason to stop. He often walked around the site after hours, looking for things that would make a great shot. On a site built to house a palace in the 12th century, there were lots of opportunities to record striking contrasts between the old and the new. Store rooms and other facilities were (and still are) tucked away in the Tower’s thick defensive walls.

Although he was a quiet man, Jeremy was fond of his colleagues, and also enjoyed interacting with the wider Tower staff. Rarely camera shy, Yeoman Warders were generally ready to assist him in getting a good picture. The ‘Beefeaters’ are still expected to live onsite with their families, and are served by a range of special facilities. These include London’s most exclusive pub, the Cross Keys, a ‘non-public house’ staffed by and only catering to resident Yeoman Warders, plus their families and guests.

Join the conversation

Thanks for sharing!