The World of the Gladiators

Rome shaped the modern world. From a small village in Italy to a bustling centre of trade and military might, the 'Eternal City' ruled over land from Britain to Iraq. The empire was home to many different people from Europe, North Africa, and Asia. They all brought their own languages, religions, and ways of life.

One of the most exciting parts of Roman life was the gladiator fights. These were contests where men, and sometimes women, fought each other to entertain crowds of cheering people.

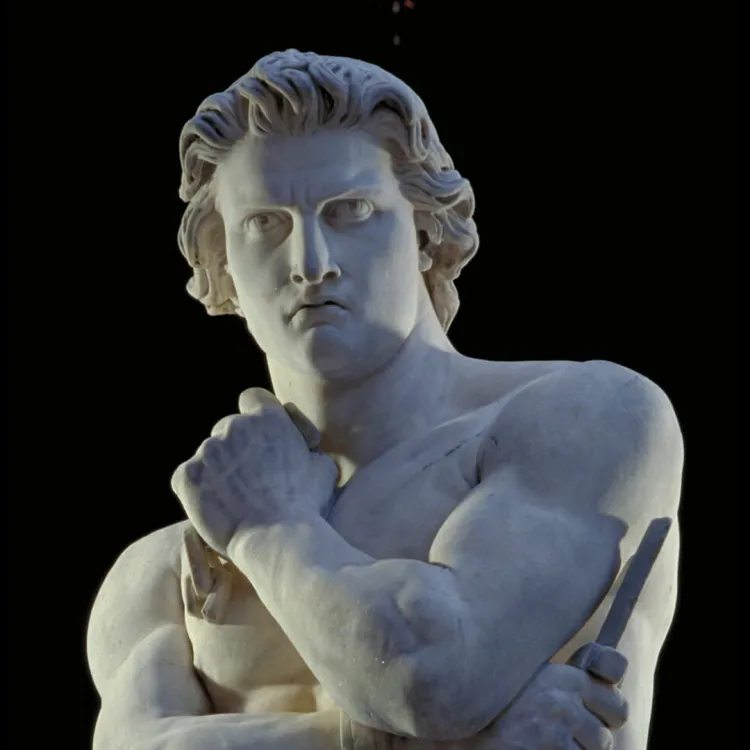

These gladiators represented the best Roman values: strength, courage, and fighting skill. Many Romans saw them as attractive and exciting, earning certain gladiators fame and fortune. Yet most gladiators were slaves, and had a very low status in society. Their profession was considered shameful and most fighters could not expect a long life.

This raises interesting questions. How did an empire built on war and slavery end up turning these slaves into heroes? And what caused the gladiator games to finally disappear?

21 minute read

History of the Gladiators

The first stone amphitheatre was constructed in Pompeii around 70 BCE. Like most amphitheatres, the one in Pompeii is a large earth bowl. Workers dug up earth to form an arena floor and piled it around the edge to form the seating area. A wall of concrete and limestone surrounded this earthen bowl, and pathways were cut to allow the gladiators in and out of the arena. The audience sat and watched the games on wooden benches installed in levels going up the sides of the earth banks. Inscriptions above the entrances tell us the amphitheatre was built by Quinctius Valgus and Marcus Porcius, magistrates of Pompeii. In 59 CE, a riot broke out in or near the amphitheatre between the citizens of Pompeii and visitors from the nearby town of Nuceria. According to Tacitus, the two sides “began with abusive language of each other; then they took up stones and at last weapons, the advantage resting with the populace of Pompeii… the inhabitants of Pompeii were forbidden to have any such public gathering for ten years”.

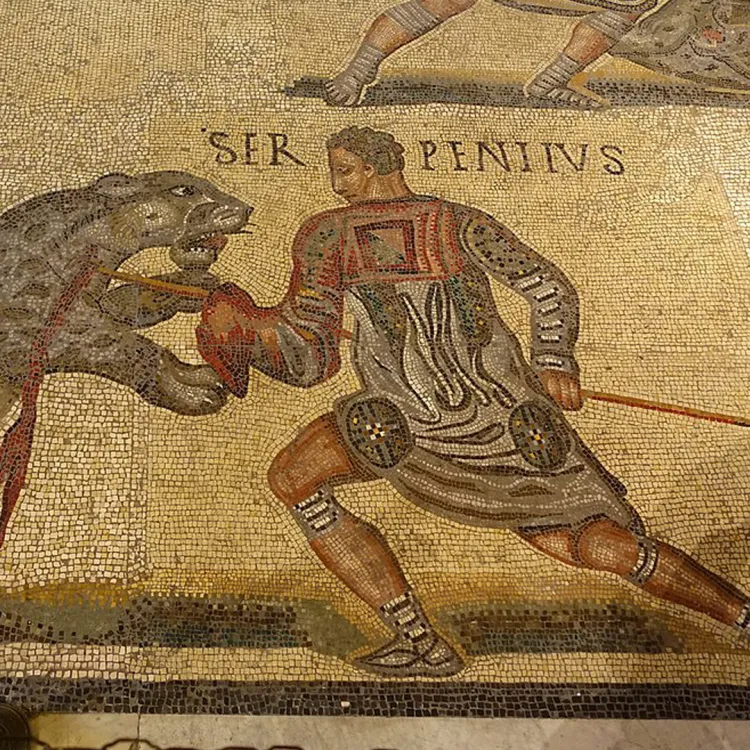

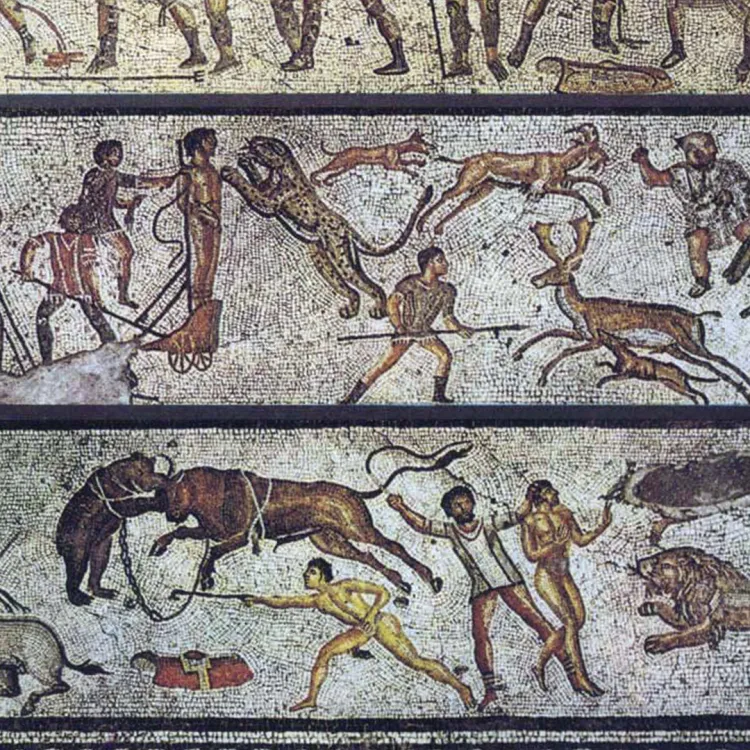

The first Roman venationes, or beast hunt, was organised by general Fulvius Nobilor in 186 BCE. To celebrate his victories in Greece, Nobilor arranged for a series of games to amuse the people of Rome. Huntsmen (venatores) fought lions and panthers and, according to Livy, the event was also the first time Greek actors and athletes performed in Rome. Exotic animals were not uncommon. As far back as 275 BCE, Roman generals put on displays of elephants captured in battle against Pyrrhus of Epirus. Beast hunts would continue to grow in popularity, reaching a height in the 1st and 2nd centuries. The opening games of the Colosseum were particularly bloody, with over 9,000 animals killed over the course of 100 days.

In 11 CE, the Roman Senate passed a decree forbidding freeborn women under the age of 20 from entering the arena. Only 8 years later, this decree was repeated, specifically banning the wives, daughters, granddaughters, and great-granddaughters of the Senate and equestrian class from the arena. The idea of female gladiators was at odds with the patriarchal society of Rome. The poet Juvenal mocks the idea in his Satires, claiming women are naturally unsuited to combat. Yet, that may have been what made gladiatrices (a modern word used to describe female gladiators) such a draw. For example, Cassius Dio mentions that the emperor Domitian would “sometimes pit dwarfs and women against each other.” Emperor Septimius Severus would later ban the practice of women, high or low-born, fighting in the arena in 200 CE in an effort, he claimed, to respect the dignity of women.

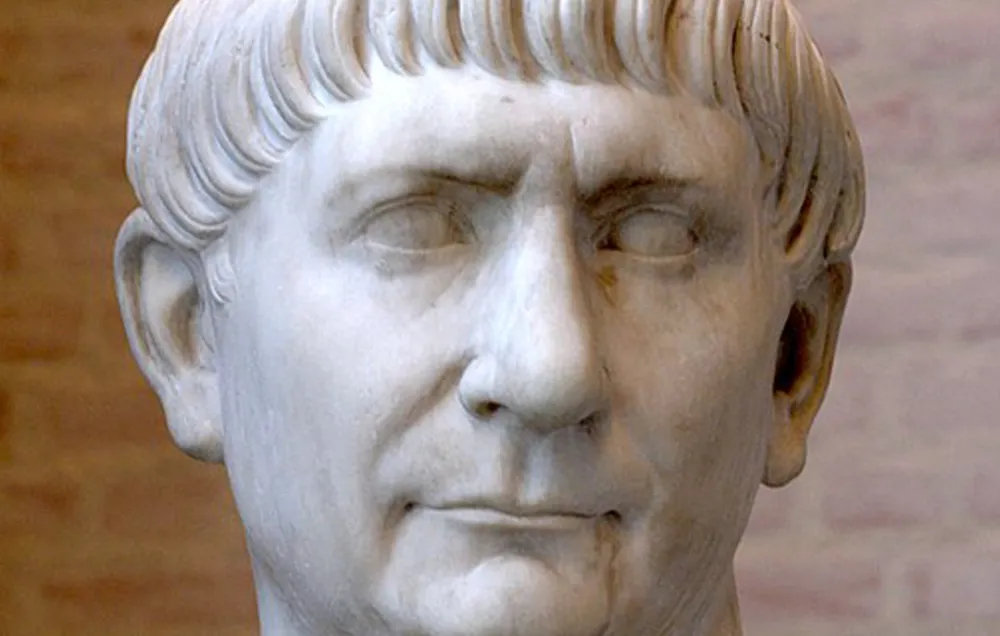

According to Cassius Dio, the largest games in Roman history occurred in 107 CE. Emperor Trajan had declared war on the kingdom of Dacia after their king, Decebalus, broke treaties with Rome. The war, now immortalised on Trajan’s Column, ended in victory for Trajan. The loot captured from Dacia was used to fund an extravagant celebration – 123 days of spectacles and games. Cassius Dio states that “some eleven thousand animals, both wild and tame, were slain, and ten thousand gladiators fought”.

The earliest evidence of gladiator matches come from a series of tombs in the city of Paestum, south of modern-day Naples. These wall paintings show various scenes from funerals in Paestum, including chariot races, boxing matches, and duels. The duels often include two fighters armed with spears, shields, and armour including helmets and chest plates. Paestum was a Greco-Italian city before coming under Roman control in 273 BCE. This is 11 years before gladiators first appear in Rome. Greek author Athenaeus, writing in the 1st century CE, however claimed Rome adopted the custom from the Etruscans – a people who lived in the north of Italy.

Gladiator fights first appear in Rome as part of funeral games to honour dead male relatives. According to Roman historian Livy, the first fight of this kind took place in 264 BCE at the funeral of Decimus Junius Brutus Pera. Roman author Valerius Maximus agrees with this account, adding that the fight took place in the Forum Boarium, or cattle market. The gladiators were captives of war and equipped in the ‘Thracian’ fighting style, with a curved sword, broad crested helmet, and square shield. The captives could have been Carthaginian as 264 BCE was also the year the First Punic War broke out between Rome and Carthage. They may have also been from the Volsinii people when their city fell to Rome that same year.

In 46 BCE, Julius Caesar returned to Rome following his victories in Gaul and Africa, and organised games for the benefit of the Roman people. As part of these celebrations, a grand mock naval battle was planned – the first reference to a naumachia in Rome. Suetonius, in his biography of Caesar, states that this battle took place on an artificial lake dug on the Campus Martius next to the River Tiber. The battle featured Tyrian (present-day Levant) and Egyptian ships, with two, three, or four rows of oars. His adopted son, Augustus, would later outdo this, staging a naumachia with 3000 captives recreating the Battle of Salamis. One of Augustus’ successors would stage an even more elaborate naumachia. On Lake Fucino, emperor Claudius arranged for 19,000 condemned prisoners to man ships in the largest recorded mock naval battle in the Roman world.

Work began on the Flavian Amphitheatre in Rome, also known as the Colosseum, around 72 CE. The name ‘Colosseum’ comes from a colossal statue of Nero as the sun god Helios placed near the site which has since disappeared. The project was conceived by Vespasian after a brief period of civil war known as the ‘Year of the Four Emperors’ (69 CE). Funding largely came from the loot secured by Vespasian following the end of the Jewish Revolt and the Sack of Jerusalem (70 CE). Unfortunately for Vespasian, the old emperor died in 79 CE before work could be completed and the project was carried on by his sons, and future emperors, Titus and Domitian. In 80 CE, Titus held the inaugural games of the Colosseum. The event was a 100-day long extravaganza, featuring gladiatorial combat, beast hunts, and executions.

Increasing financial burdens brought by internal and external wars, as well as changing public opinion, led to a decline in games offered by the state. Constantine I rose to the rank of Augustus in 306 AD and made Christianity a tolerated religion by the Edict of Milan in 313 CE. Bishops and clerics, who had objected to the practice, began actively campaigning for the end of the gladiatorial spectacle. Constantine abolished the condemnation of prisoners to the arena in 325 CE, yet gladiatorial combat continued. In 354 CE alone, a surviving calendar indicates that ten days were reserved for gladiator shows. This was not the end of the games, but it did mark the beginning of the end of the gladiatorial system.

Emperor Honorius is believed to have closed the Ludus Magnus, the largest gladiator training school in Rome. The Ludus Magnus in Rome was a building adjacent to the Colosseum devoted to training and supplying gladiators. It was the largest of four imperial gladiator schools in Rome built during the reign of Domitian (81-96 CE) and could hold 3000 people to watch the gladiators prepare for battle. Excavations uncovered 14 housing cells of 20 square metres each, and the entire school is thought to have held 1000 gladiators. After the closure, the Ludus Magnus fell into disrepair and was used as a cemetery until it’s eventual rediscovery in 1937.

After a period of gradual decline, emperor Honorius formally bans the practice of gladiator matches in 404 CE. One story of why this happened follows a Christian monk called Telemachus. During a gladiator match, Telemachus jumped into the arena and pleaded for the killing to stop. The crowd was so angry at this interruption that they called for the gladiators to turn on Telemachus, and they killed him. Honorius admired Telemachus’ bravery and ended the tradition there and then. Whether or not this happened is unknown. The practice of gladiator fights may have continued sporadically until the reign of Honorius’ nephew Valentinian III in the mid-5th century. We do not know when the last gladiatorial contest took place. A call to ban public entertainment by a Christian bishop in 440 CE mentions chariot racing and beast hunts, but not gladiators. This implies the practice was already dying out.

In 523 CE, Cassiodorus, a senator under the Gothic King Theodoric, gives us the last mention of a state authorised beast hunt. Cassiodorus condemned the practice, complaining to a consul, “Alas for the pitiable error of mankind! If they had any true intuition of Justice, they would sacrifice as much wealth for the preservation of human life as they now lavish on its destruction.” The venationes, or beast hunts, continue in the Eastern Roman Empire in the sixth century, but the displays had changed from deadly hunts to tests of bravery by evading dangerous beasts. The practice was not officially abolished until 681 CE.

A Day at the Games

Much like football matches today, gladiatorial games were not just days out but a glimpse into the Roman world. Outside the amphitheatre, street vendors sold merchandise to visitors and local bars fed and watered thirsty fans of the games. Inside the arena, seating was based on your wealth and status in society. Meanwhile the Roman upper classes took the opportunity to show off their power and generosity. Step back in time to Roman Britannia and experience for yourself what it may have been like to spend a day at the games with our immersive audio play.

Download the transcript of A Day at the Games (Word, 22.49 KB)

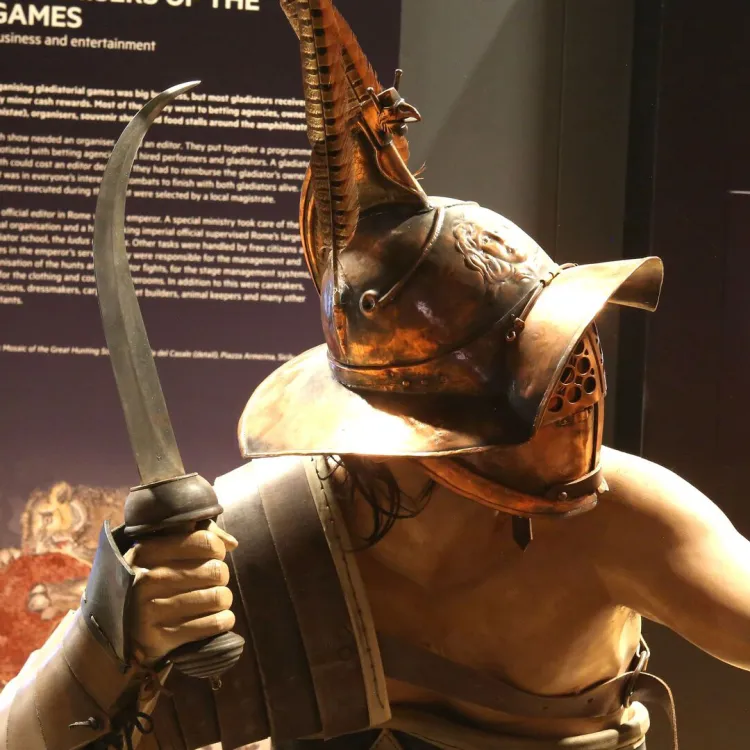

Types of Gladiators

Gladiatorial combat existed for over 6 centuries. In that time, the types of gladiators that faced each other in the arena changed as fashions came in and out of style. The greatest change came with the fall of the Roman republic in the 1st century BCE. The emperor Augustus implemented a series of reforms to the games that were well documented. By that time, gladiator styles such as the Samnite and the Gaul were being replaced by forms more familiar to us today, such as the Murmillo and Thraex. There was also very little change to these types throughout the empire, pointing to a standardisation of gladiators that continued from 1st century CE to 4th century CE. Here are a few of the most well-known gladiator types and the arms they wielded.

Gladiator Roster

Meet the Gladiators

In 2004, archaeologists in York made a fascinating discovery. A Roman cemetery containing the remains of mostly young men who appeared to have lived hard and violent lives. A significant portion of them had been beheaded, and one unfortunate soul in particular appeared to have been bitten by a big cat, such as a lion. How did these men come to this unpleasant fate? And do they point to a large entertainment business that supplied gladiators and animals to the far-flung corners of the Roman Empire? Join us as we gain unique access to one of the bodies and meet the gladiators of Roman York.

With thanks to York Archaeological Trust.

Women of the Arena

Rome was a male-dominated society, with strict roles expected of both men and women. The gladiatrix was a challenge to the norm of Roman society. Yet the public, and some emperors, also found the idea of female fighters exciting and exotic. Charlotte Bell of the University of Liverpool dives into the subject of gladiatrices and explores the history of these enigmatic figures.

Opposition to the Games

Gladiatorial combat existed in the Roman world for over six centuries. Beginning life as a solemn graveside ritual, the practice ballooned into an ever more elaborate form of entertainment that attracted thousands of people. Yet love for the games was not universal. Certain influential Romans, such as the philosopher Seneca, viewed the games as beneath them, an amusement for the plebeians. The poet Juvenal described how the once democratic citizens of Rome gave up their rights in return for nothing more than bread and circuses. Public disgust of the bloodletting became more evident with the rise of Christianity, with early Christian figures such as Clement of Alexandria describing the arena as ‘the seat of plagues.’

Famous Gladiators

Gladiators represented a struggle at the heart of Roman society. On the one hand, they were warriors who embodied the Roman virtues of strength and courage through combat. On the other hand, gladiators were still slaves to be bartered, used, and sold at will. Ultimately though, a good performance in the arena could earn a gladiator fame, fortune, and even freedom. As with professional athletes today, the Roman public idolised these fighters and immortalised their heroes through graffiti and murals. From scandalous emperors to husbands cut down in their prime, here are just some of the gladiators whose names have been passed down to us.

Join the conversation