Spartacus

The Gladiator who Defied an Empire

The legend of Spartacus and the Third Servile War has etched itself into popular memory, from classic films, to TV series, to video games. But the information we have on Spartacus is remarkably light and comes from a collection of Roman and Greek scholars writing several decades after his death. Plutarch, Sallust, and Appian all give accounts of The Third Servile War, corroborating details about the campaigns and the prominent Romans who fell in battle. Yet, beyond a few introductory lines, little is known about the gladiator himself. So, who was Spartacus? And how did he rise from Thracian slave to the general that nearly brought Rome to her knees?

17 minute read

Spartacus and the Third Servile War

Spartacus, Thrace, and Slavery

“At the same time Spartacus, a Thracian by birth, who had once served as a soldier with the Romans but had since been a prisoner and sold for a gladiator, and was in the gladiatorial training school at Capua, persuaded about seventy of his comrades to strike for their own freedom rather than for the amusement of spectators”

Appian, The Civil Wars

Almost all accounts about Spartacus agree on one thing. He was Thracian. Located in modern day Bulgaria, Thrace was a collection of Balkan tribes and kingdoms whose frequent infighting had been their undoing for centuries. Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BCE, claimed that – “If they were under one ruler, or united, they would, in my judgement, be invincible and the strongest nation on earth.”

Thrace historically existed on the fringes of great empires. During the Greco-Persian Wars, King Darius I marched overland through Thrace on his way to battle the Greek city states. When Macedonia was on the rise under Alexander the Great, Thracian kingdoms and tribes, such as the newly formed Odrysian Kingdom, were enlisted into his great campaigns in the east . During this time, Thrace became a crossroads for the trade in human labour, slaves, trafficked from the Black Sea and the east. A trade that was increasingly fed by Rome’s eastern military expansion in the 2nd century BCE.

The Thracian tribes however clung to their independence. Macedonian kings such as Philip V led repeated punitive raids into Thrace to stop attacks on their territory. When Philip V supported Rome in their campaigns in Asia Minor in 190 BCE, we have some of the first evidence of Thracians coming into conflict with Roman soldiers. Later, Livy tells us how the Thracian Odyrsian Kingdom donated about 1,000 cavalrymen and 1,000 infantry soldiers to the Macedonian war with Rome. Even when Rome officially made Macedonia a province, their relations with Thrace were fractious at best. Thracian tribes from the interior of the region continued to raid Roman territory, occasionally killing an important Roman in the process. Rome would reply with punitive wars against hostile tribes, enlisting friendly Thracians as auxiliaries.

But how would these Thracian warriors have been armed and armoured? Painted figures from tombs dated to 3rd century BCE indicate they bore armour similar to their Greek and Macedonian neighbours, but not the same. The Greek aspis or hoplon was rare in Thrace. A more common shield would have been the Thueros, which was oval with a central wooden or bronze rib. Other pieces of protection would include the Chalkidian or Phyrgian helmet, iron or linen cuirasses, and greaves. Scholars such as Christopher Webber have noted that these appear to have remained in use long after they had fallen out of fashion in their regions of origin.

At the same time, the Thracians were also renowned for their light cavalry skills, specifically their ability to skirmish with the enemy. The Roman author Curtius mentions how, “Alexander (the Great) sent the Agrianes and Thracian light-armed against the elephants, for they were better at skirmishing than fighting at close quarters. These released a thick barrage of missiles on both elephants and drivers.”

Later, tribes and kingdoms allied to Rome, such as the Thracian King Rhoemetalces, would have made their people familiar with Roman arms and discipline. The Roman historian Florus also writes that Thracians were equipped “in the Roman style”, which may mean mail shirts and legionary helmets. Thracians were also famous for the use of curved swords such as the rhomphaias, the kopis, or the sica. They may have also been armed with javelins to harass the enemy.

This was the world – caught between Rome and Greece, between traditional Thracian warfare and Roman discipline - that Spartacus would have been born into.

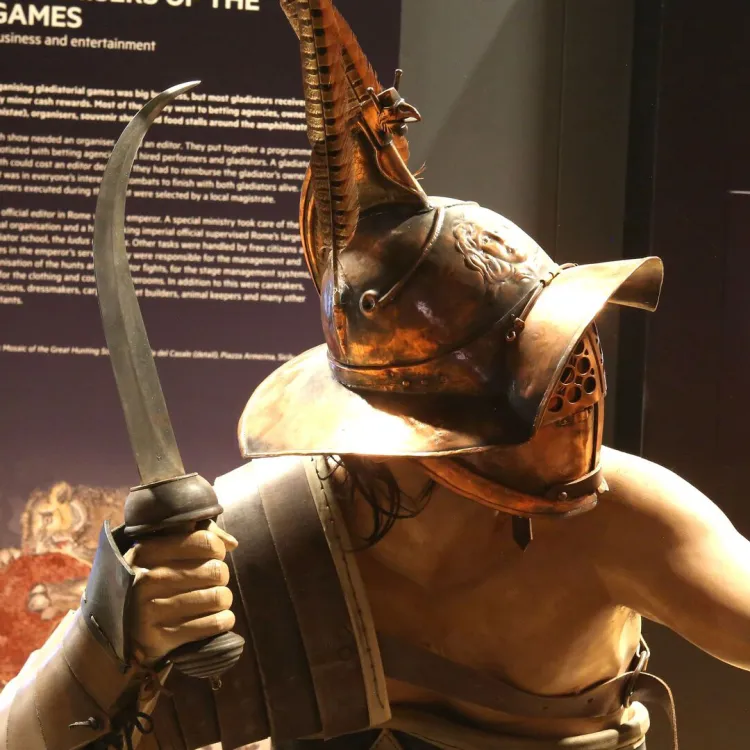

The Life of a Gladiator

“A certain Lentulus Batiatus had a school of gladiators at Capua, most of whom were Gauls and Thracians. Through no misconduct of theirs, but owing to the injustice of their owner, they were kept in close confinement and reserved for gladiatorial combats.”

Plutarch, Life of Crassus

However Spartacus arrived in Italia, Plutarch and Livy agree that he was sold to the ludus, or gladiatorial school, of Lentulus Batiatus in Capua. If little is known about Spartacus, even less is known about his master Batiatus. It has been suggested that the Batiatus of legend is Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus Vatia, who was a prominent noble of Rome. Capua is in the region of Campania, in southern Italy, and was an important colony of Rome in the 1st century BCE. Cicero described it as a ‘second Rome,’ and is where some of the first evidence of gladiatorial combat in the Italian peninsula is found. Throughout the turmoil of the Servile Wars and the Social War in the first half of 1st century BCE, Capua and Campania remained an important hub for gladiatorial training.

The life of a gladiator was hard. Before a beginner gladiator, or tirones , could enter the ludus, they would be required to take an oath of loyalty to the lanista. When they begun training, a novice would be very low in the gladiatorial hierarchy and would have to prove themselves as valuable assets. Their clothes, foods, and living quarters would have varied around the empire. The Ludus Gladiatorius in Pompeii for example, consisted of a large rectangular courtyard onto which many individual rooms opened. Each narrow room was only 10 – 15 metres square and had no bed to speak of. Gladiators likely slept on straw mattresses. In addition, the ludus had a prison where inhabitants could not even stand.

According to the physician Galen, who was a doctor at a gladiatorial school in the 2nd century AD, bean soup and barley formed most of a gladiator’s diet. He also mentioned the severe physical toll that came with athletic training, “limbs (were) broken or dislocated, and eyes gouged out of sockets show the kind of beauty produced. These are the fruits they gather”.

The Roman philosopher Epictetus explained athletes should, “conform to rules, submit to a diet, refrain from dainties; exercise your body, whether you choose it or not, at a stated hour, in heat and cold; you must drink no cold water, and sometimes no wine.” This regime, designed to train athletic, highly skilled fighters, could take a severe toll on the body. At the same time, gladiators were considered infames; a shameful designation that deprived them of certain rights and protections. During the Republican era, this may mean non-slave infames could not vote. Under the emperors, the legal repercussions extended to being prevented from writing a will or bringing criminals cases to court.

Despite this, gladiators were significant investments for their lanistas, or managers. Gladiators could expect sophisticated medical treatment and living quarters of better quality than many freeborn Roman citizens. We have gravestones that show gladiators could form long lasting relationships and have their partners in the ludus with them. This is the case with Spartacus, who was said by Plutarch to have had a wife who served at Batiatus’ ludus and escaped with him.

If Spartacus was put through this arduous training regime, we know very little about his success as a gladiator. The best evidence we have for a gladiator called Spartacus is from surviving graffiti in Pompeii that dates to between 100 BCE and 70 BCE. This shows a mounted gladiator, an eques, with the name “Spartaks” inscribed above his head. There is no mention of his victories or losses in the arena unfortunately. Although Sallust describes Spartacus as being ‘immensely strong’, most ancient sources were just not as interested in Spartacus the gladiator compared to Spartacus the rebel leader.

The Beginning of a Rebellion

“Seventy-four gladiators escaped from the school of Lentulus Batiatus at Capua, and, collecting a large number of ordinary slaves as well as those kept in slave barracks, they began to wage war under their leaders, Crixus and Spartacus. They defeated the legate Claudius Pulcher (Glaber) and the praetor Publius Varenus in battle”

Livy, Summaries

From the outset, three gladiators emerge from multiple sources as the leaders of the slave revolt - Crixus, Oenomaus, and Spartacus. Spartacus is singled out by Plutarch however as different from both his fellow gladiators and the Thracian people he came from. He described Spartacus as strong and spirited, but also intelligent and cultured, “being more like a Greek than a Thracian.” Despite Spartacus’ low status, he is repeatedly hailed by ancient sources as possessing something that made him different to other slaves. This supports an ingrained belief in the Roman world that ‘barbarians’, that is anyone who wasn’t Greek or Roman, were inherently uncivilised.

From the initial group of 50 to 100 fugitive gladiators, the rebel ranks swelled to over 120,000 armed soldiers . Where did Spartacus find this army? Appian offers us a clue. In his history of the Roman civil wars, he tells us, “Many fugitive slaves and even some free men from the surrounding countryside came… to join Spartacus.” Roman agriculture was based on the latifundia, or farming estates, which were owned by wealthy men in Rome but worked by large slave populations. In the 1st century BCE, after Rome had undergone a series of wars and rebellions, the slave population boomed as war captives were condemned to work as gladiators, farmhands, or other manual labourers.

Appian explained that the small force led by Spartacus raided nearby villages and farms, although whether this was to seize food and money or to liberate the slave populace, isn’t clear. It is not difficult to imagine that disgruntled slaves under attack by Spartacus would happily turn on the Romans themselves.

Another question asked is how a band of gladiators and slaves could take on, and defeat, two Roman armies? Appian argued that the Romans at first did not take the threat seriously, putting the legate Gaius Claudius Glaber and the praetor Publius Varinius (magistrates and military commanders) into the field. “These men did not command the regular citizen army of legions, but rather whatever forces they could hastily conscript on the spot.” Sallust supported this argument, saying the quality of troops was poor, with most of them either ill, deserted, or simply refusing to follow orders.

By contrast, Spartacus seemed to have had a strong head for tactics. In one story by Plutarch, Glaber laid siege to Spartacus’ army camped on Mount Vesuvius. Instead of surrender, the rebel slaves used vines to clamber down difficult or impassable cliff faces. “The Romans were wholly unaware of these developments. Consequently, the slaves were able to surround them and to shock the Romans with a surprise attack.” The precise size of the band of disaffected gladiators and slaves who attempted this feat isn’t clear.

From the slopes of Mt. Vesuvius, Spartacus then marched south towards Metapontum, where, we are told, he began turning his band of slaves into an army. Was Spartacus intent on destroying Rome? Was vengeance his primary motivator? Not according to Plutarch. Spartacus apparently knew he could not take on the might of Rome, and instead marched his army north, past the Eternal City, towards the Alps. The intention was to lead his slaves to freedom and back to their homelands.

Missed Opportunities

“Once they crossed the mountains, he thought that it would be the best, indeed the necessary, course of action for the men to disperse to their own homelands, some to Thrace and others to Gaul. But his men, who now had confidence in their great number and had grander ideas in their heads, did not obey him.”

Plutarch, Life of Crassus

There was one small problem. Sallust and Plutarch both mention a breakdown between Spartacus and fellow general Crixus. Crixus wanted to tackle the Romans head on, and in his “insolent arrogance” took between 20,000 and 30,000 men to “pillage Italy far and wide”. In Rome, this was enough of an alarm bell for the Senate to send both their consuls, the highest elected political office, to put down the rebellion. As Crixus passed by Mt. Garganus (now Gargano) in southern Italy, Plutarch tells us that consul Lucius Gellius Publicola ambushed the slaves. Crixus, together with almost all his men, were killed. When Spartacus heard of this defeat, he ordered 300 Roman prisoners to fight to the death – a grim reversal of the origins of Roman funerary rites where gladiators were expected to spill blood to honour the deceased.

Spartacus resumed his march north, and sources differ on his precise course of action. What is agreed upon is that Spartacus defeated the second consul, Gnaeus Cornelius Lentulus, on his journey towards the Alps. Waiting for him was the governor of Cisalpine Gaul, Gaius Cassius Longinus, who was said to have had “a myriad” of soldiers, or exactly 10,000 men. The battle at Mutina (modern day Modena) was hard and bloody. Plutarch explained that “Cassius was defeated, with the loss of many men”. Again, the sources disagree on certain points. Plutarch, writing in the 2nd century CE, asserted that Cassius escaped “only with difficulty”, whereas Orosius, writing in the 4th century CE, claimed that Cassius was killed. It is a good example of how evidence for Spartacus and the Third Servile War relied on different interpretations of older sources.

Whatever happened to Cassius, the road across the Alps and towards freedom was now open to Spartacus. Yet, they didn’t make the crossing. Instead, Spartacus and the army wheeled south back down into Italy. Neither Plutarch, Appian, nor Sallust gave a reason for this change of heart. Was Spartacus’ army too weak to make the journey? Or did they give in to “their servile nature” and think “of nothing but blood and booty”? It isn’t made clear. What is clear is that the rebels returned to southern Italy and chose to occupy the city of Thurii – an old Athenian colony in the modern province of Cosenza. Rome, meanwhile, was not standing idle. The Senate angrily recalled the consuls who had failed to put down the rebels and instead turned to someone rich enough and capable enough of defeating Spartacus once and for all.

Marcus Licinius Crassus

“And when he rearmed Mummius’ soldiers, Crassus demanded formal promises from them that they would not “lose” their weapons. What is more, Crassus selected five hundred of the soldiers who had been the first to run from the field of battle… and divided them into fifty groups. He then executed one man who had been selected by lot from each group.”

Plutarch, Life of Crassus

By 71 BCE, Marcus Licinius Crassus was said to be one of the wealthiest men in Rome. Plutarch is one of our chief sources. In his biography of Crassus, Plutarch stated, “the many virtues of Crassus were obscured by his sole vice of avarice” and he possessed a fortune of 7,100 talents of silver. This great wealth was gained from various shady business dealings. This included the purchase of houses on fire at knock down prices, and receiving property from the dictator Sulla (82 – 79 BCE).

Plutarch also tells us that Crassus believed a man was not truly wealthy until he could fund an army alone. This was to be put to the test following Spartacus’ victory over Cassius. Appian explained that when it came time to appoint a new commander, no one volunteered out of fear of the same disgrace that their predecessors had suffered. Only Crassus put his name forward, and with 6 fresh legions behind him, the newly appointed commander set off toward the province of Picenum in central Italy. According to Plutarch, Crassus’ first move was to shadow Spartacus, sending his legate Mummius with two legions to circle around the rebels. Mummius, however, was not a patient man and rushed to engage Spartacus as soon as possible. “Many of his men were killed”, recorded Plutarch of the battle, “and many others dropped their weapons and ran from the field.”

It is here that Crassus is recorded as resurrecting an old, and cruel, form of punishment for the over-eager legions: decimation. One soldier in ten was selected by lottery for execution, to deter the remaining nine from further disobedience. Plutarch and Appian disagreed on the total number of men killed, but Appian mentioned that the result was to make “himself (Crassus) more fearful than the enemy to his own men.” Spartacus meanwhile continued his march south back towards the Strait of Messina between Sicily and the mainland. Here, Plutarch explained, Spartacus hatched an ambitious plan to invade Sicily and stoke the fires of rebellion there too. He even hired Cilician pirates to transport his army across the straits towards Sicily.

The island was the birthplace of two previous slave uprisings which posed significant challenges to Rome. The governor of Sicily during the Spartacus revolt, Gaius Verres, was certainly aware of this. The Roman lawyer and orator Cicero recorded that Verres brutally put down any hint of rebellion on Sicily, “He actually appears to have extinguished the fire that was beginning to spread with the suffering and deaths of only a few victims”. So, what was Spartacus’ motivation for moving to Sicily? It isn’t clear. Florus claimed that the manoeuvre was to avoid being trapped in the toe of Italy. This was also supported by Sallust, although the account of this period is incomplete. Plutarch however claimed that Spartacus tried to “seize Sicily” and that by landing 2,000 of his men on the island, the flame of rebellion would be rekindled. Again, Spartacus’ motivations remain unclear.

Events were rapidly turning against Spartacus. The Cilician pirates, we are told by Plutarch, betrayed the rebels and sailed away. Meanwhile, Crassus constructed a vast wall across the peninsula to keep Spartacus under siege. Excitingly, there appears to be archaeological evidence for this. In 2024, a team from the Archaeological Institute of America discovered a stone wall and earthwork extending over 2.7 km in south Calabria in Italy. Plutarch stated the wall, “ran from sea to sea, across the narrow neck of land, for a length of 300 stades (56 km)”. According to Appian, “Spartacus decided to make one last desperate attempt… he made a charge directly through the line of Crassus’ wall and ditch with his entire army”. The discovery of broken iron weapons, including javelin points and curved blades, at the site of the ruins point to a battle taking place there.

The Death of Spartacus

“When his horse was brought to him, Spartacus drew his sword and shouted that if he won the battle, he would have many fine horses that belonged to the enemy, but if he lost, he would have no need of a horse. With that, he killed the animal. Then, driving through weapons and the wounded, Spartacus rushed at Crassus. He never reached the Roman.”

Plutarch, Life of Crassus

Time was running out for Spartacus. The siege and breakout from Crassus’ wall had cost the rebels dearly. Internal squabbles appeared to divide Spartacus’ forces even further. Furthermore, Roman reinforcements were descending on southern Italy. This, according to Plutarch and Appian, made Crassus even more aggressive as he became determined to claim victory alone. With dwindling numbers and facing potentially three Roman armies, Spartacus made the fateful decision to stand and fight. Appian stated it was out of desperation. Plutarch says it was out of arrogance. Either way, the final battle took place on the banks of the Silarus River in Campania.

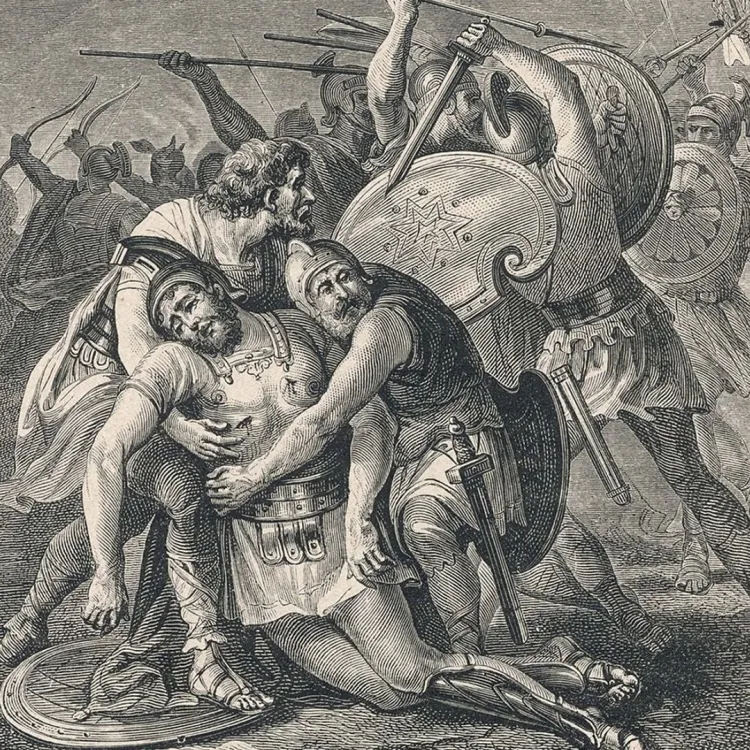

The battle, according to Plutarch, was chaotic. Crassus attempted to dig a defensive ditch, but the slaves, no longer obeying their leaders, charged into the ditch to fight the Romans. Seeing the situation grow out of his control, Spartacus was alleged to have killed his horse, claiming that should he survive, he would have the pick of all the horses captured from the Romans. With that, the rebel leader charged at Crassus himself and killed two centurions before being cut down himself. Appian’s account is slightly less dramatic, saying that Spartacus received a spear to the thigh. Injured, he fought off his attackers for as long as he could before dying in battle. With the collapse in leadership, the slave army disintegrated. The killing was on such a scale, according to Appian, that it was impossible to count the dead. Plutarch, however, gave a figure of around 12,300 slaves killed. Livy claimed 60,000 slaves died. Orosius gave the highest total, with 100,000 rebels who died in battle. Spartacus’ body was never found.

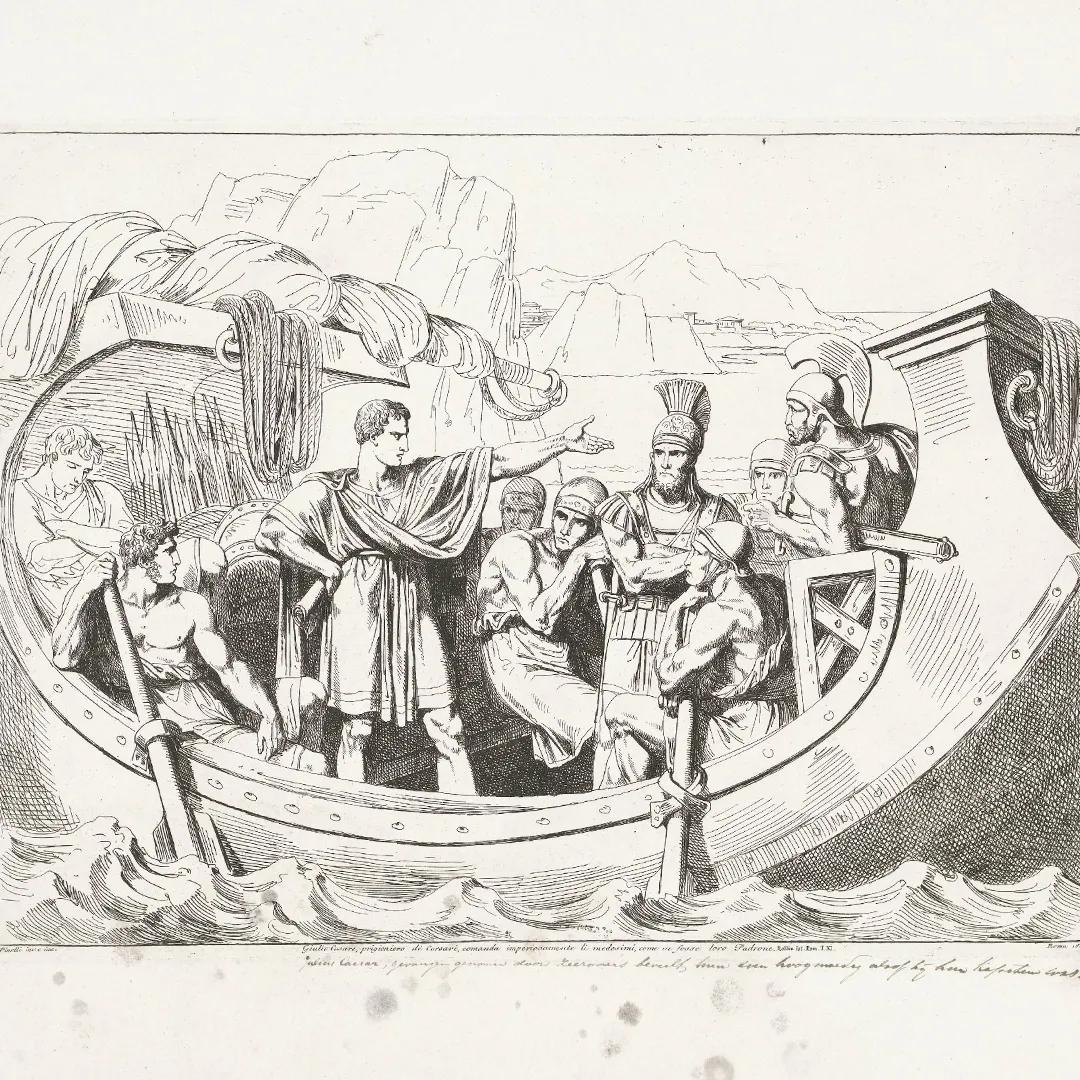

Some 6,000 slaves were said to have been crucified along the Appian Way following the battle. For his efforts against Spartacus, Crassus was to be denied the military acclaim he wanted. Plutarch tells us that as Crassus was defeating the bulk of the rebel army, a force of 5,000 fleeing slaves encountered another great Roman general, Gnaeus Pompeius Magnus, or Pompey the Great. Fresh from victories in Spain, Pompey then wrote to the senate to claim that “although Crassus had defeated the gladiators in battle, he (Pompey) had extinguished the war to its very roots.” Pompey received a triumph for his military achievements in Spain and Italy. Crassus received the lesser accolade of an ovation. This, Appian stated, resulted in “the sudden emergence of a bitter competition for honour between Pompey and him (Crassus)”. A rivalry that would lead to the forming of the First Triumvirate between Crassus, Pompey, and a young nobleman called Julius Caesar.

Join the conversation