The Hundred Years' War

The Hundred Years' War (1337 - 1453) was a prolonged struggle between the rival kingdoms of England and France.

Rather than being one long war, the Hundred Years' War was actually a series of sieges, raids, and battles on land and sea as the two countries competed for control of France. It grew out of centuries of bickering over the lands which English kings held in France, to which was added in the 1330s an English claim to the French crown itself.

In 1337, Philip VI of France invaded the French lands of Edward III of England, triggering a territorial war between the two kingdoms. Edward responded in 1340 by claiming the throne of France itself! The struggle was now for a crown. Both men were related to the previous French king: Edward was his sister's son and Philip was his cousin through the male line. The rivalry drew in other kingdoms as well, as Philip had already challenged Edward by giving support to the Scots in their struggle against English domination.

The conflict saw many significant changes in the ways that countries waged war, and the weapons they used. Improvements in infantry training and equipment proved vital. Archers in particular, who had been trained to use their longbows since youth, used their weapons to devastating effect throughout the campaigns.

Technological innovations such as plate armour, early artillery, and the first firearms frequently made the difference between victory and defeat, of life and death.

Army recruitment was similarly transformed. To wage long campaigns in France, the English developed professional armies raised by contracts between captains and the crown. Both sides sought the support of allies and men from all over Europe joined the armies as soldiers. During the intermittent periods of peace, English and French soldiers joined the Great Companies of mercenaries, willing to fight anyone for money.

Leading personalities emerged, including Joan of Arc, Henry V, and Edward 'the Black Prince' - names that still resonate today.

48 minute read

Key battles and events

The first battle of the Hundred Years' War was at the harbour of Sluys. This naval engagement was an important English victory that virtually destroyed the French fleet and crushed Philip VI's plans to invade England.

When Edward III set sail for France in 1340, his army was greeted by a French fleet of over 200 ships waiting at the harbour of Sluys. Although the French outnumbered the English, Edward's ships had greater manoeuvrability.

The battle began with volleys of arrows, after which the French ships, which had been chained together, were boarded and hand-to-hand combat commenced. With the fleet unable to escape, many French ships were boarded, and many soldiers were drowned.

The Battle of Crécy was the first land battle of the Hundred Years’ War, and a decisive English victory.

Prior to the battle, Edward III's English army had launched a raid from Barfleur eastwards across Normandy and briefly captured the town of Caen before marching towards Paris. The French army, led by King Philip VI, aimed to trap the English as they moved north and crossed the River Somme. In response, Edward positioned himself on a ridge near the town of Crécy and waited for battle.

By the time the French arrived, they found they could not outflank Edward. Genoese crossbowmen in the French army began a premature advance but were struck by arrows from the English longbowmen and forced to retreat. French knights charged through the retreating crossbowmen and directly into a hail of English arrows. Repeated cavalry charges met with the same fate and failed to break the English lines. The French were emphatically defeated, with many casualties.

After his victory at the Battle of Crécy, Edward III marched north with his army to besiege the port town of Calais, which he considered would provide a useful base for future invasions of France. Reinforcements and food were brought in from England.

The siege took over a year and Edward built a fortified town – Villeneuve-le-Hardi – outside Calais to maintain the encirclement. The city was only taken after the inhabitants had been starved into submission and a French force failed to relieve the defenders. The citizens were evicted and replaced with English settlers, in a scene that gave rise to the story of the burghers of Calais, later immortalised by a bronze sculpture by Rodin.

In 1347, the Hundred Years’ War was halted by the horrors of the Black Death. As a result, there were to be no large-scale campaigns or battles until 1355.

This epidemic of bubonic plague is believed to have arrived in Southern Europe from merchant ships, and carried by the fleas of black rats.

The people of Europe did not have the medical knowledge to understand or treat the disease and believed it to be a punishment from God. Estimates claim that it stole the lives of millions of Europeans.

Edward III's son – Edward the 'Black Prince' – had ‘won his spurs’ at the Battle of Crécy. He became one of the most successful commanders of the Hundred Years’ War.

He went on to launch a brutal and devastating raid, known as a chevauchée, through the French countryside in 1355. Raids of this sort not only terrorised French citizens and crushed morale but also discredited the French army, the French king, and destroyed valuable resources.

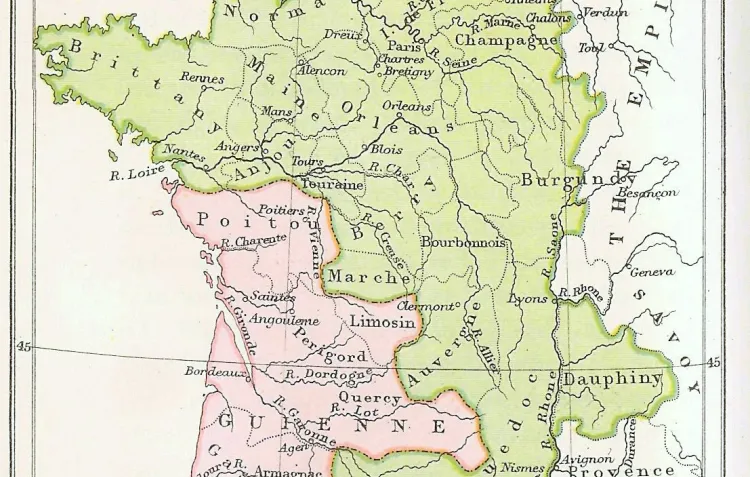

Edward's harrying and wasting of the country occurred in the region between Bordeaux on the Atlantic coast of France and Narbonne close to the Mediterranean. Edward and his army covered a distance of some 402 kilometres (250 miles) in just over a month.

The Battle of Poitiers was fought between the armies of Edward 'the Black Prince' of England and John II of France.

Edward had launched a second devastating raid (chevauchée) northwards from Bordeaux in 1356. The French intercepted him in September 1356 near Poitiers and Edward chose a hedged area to protect his troops.

The first French cavalry charge attempted to strike the English through a gap in the hedge. English longbowmen were waiting on the other side and loosed their arrows into the rumps of the French knights’ horses.

Two further charges followed, resulting in brutal hand-to-hand fighting. A third French charge also failed, and King John was left stranded. He surrendered to Edward and was taken prisoner. The capture of John was a major cause of the Treaty of Brétigny in 1360, which ceded over a third of France to King Edward III.

In May 1360, over four years after the French king was captured at the Battle of Poitiers, the Treaty of Brétigny was confirmed. Edward III agreed to give up his claim to the throne of France in return for huge territories in south-west France and for Ponthieu and Calais to be held by him absolutely, without French overlordship.

After the Treaty of Brétigny (1360), England and France achieved a measure of peace but in 1369, Charles V of France invaded English lands. Edward III once more took up the title of king of France. Despite the loss of most of the lands won in 1360, a truce was negotiated in 1389. The peace was broken when Henry V of England, Edward's great-grandson, declared war and laid siege to the port town of Harfleur in Normandy.

The Battle of Agincourt is the most well-known battle of the Hundred Years’ War. Henry V was aiming to return to Calais but was intercepted by a French army which blocked his route.

By provoking the French army to attack, Henry was able to use defensive tactics offensively. Protected by wooden stakes driven into the ground, the arrows of English longbowmen broke the French men-at-arms, who were further disadvantaged by the muddy ground. The French cavalry failed in their charge against the archers.

Agincourt was a swift victory. French casualties were far higher than the English, and many French were captured, including the dukes of Orleans and Bourbon.

The battle was immortalised by Shakespeare in his play King Henry V, which has ensured the battle’s iconic status.

Henry V's final triumph was in May 1420 when he was accepted as heir and regent of France through the Treaty of Troyes.

Three years earlier, Henry had invaded Normandy again intending to conquer it. He took cities and towns such as Caen, Falaise and Rouen - the latter after a siege of six months. The French failed to unite against him. In September 1419, the Dauphin’s men assassinated John the Fearless, duke of Burgundy. As a result, the new duke, Philip, sought an alliance with Henry. The French king, Charles VI, was forced to accept the English claim to France. The Treaty of Troyes, sealed on 21 May 1420, ensured that Henry would succeed to the French throne upon Charles’s death, in place of the Dauphin. Henry married Charles’s daughter Catherine.

Henry died shortly before Charles in 1422, and therefore it was the nine-month-old Henry VI, Henry and Catherine’s son, who became king of both England and France.

The Battle of Verneuil was a strategically important English victory. It strengthened English control over Normandy, but was also one of the bloodiest battles of the Hundred Years’ War.

John, Duke of Bedford, and regent for the infant Henry VI, led the English army. The French army consisted of an allied force of French, Scottish and Lombard soldiers.

After an opening archery duel, the French seized their opportunity and the heavily armoured Lombard cavalry smashed through the English lines. This initially caused chaos; the Lombards mowed down some of the archers and endangered the baggage train before being repulsed. Bedford regrouped and launched a ferocious counterattack on the French infantry, beating them back after a bloody battle.

Bedford surrounded the remaining Scots, who were regarded as rebels and to whom no quarter was to be given. Many of their leaders were killed.

The siege of Orléans marked a turning point in the Hundred Years’ War. The French, rallied by Joan of Arc, claimed a major victory that reversed English ascendancy.

The English besieged the well-fortified city of Orléans from 12 October 1428. For several months the garrison held out, but the English appeared to be gaining the upper hand after defeating French efforts to intercept their supply train (Battle of the Herrings, Feb 1429).

The French needed inspiration, which came with the arrival of Joan of Arc. She had persuaded the Dauphin Charles that she had received a divine mission to regain his throne and expel the English.

On 29 April 1429, Joan entered Orléans with some 200 men-at-arms. On 6 and 7 May, she led successful assaults against English positions. The English conceded defeat on 8 May and withdrew. On 18 June, they were defeated in battle at Patay.

Joan proved a successful leader. Many places surrendered to her, allowing the Dauphin to enter the traditional crowning place of Reims and to be crowned as Charles VII on 17 July 1429.

In 1430, Joan was captured by the Burgundians who sold her to the English, who in turn handed her over to the church to be tried for heresy. Initially she accepted the judgement of the court, but then relapsed and was given over to the secular authorities to be burned at the stake in Rouen in May 1431. She was just nineteen years old.

In 1456, when Rouen was again in French hands, she was retried and the sentence of 1431 annulled. In 1920, she was made a saint.

In 1435, the Duke of Burgundy defected to the French. The following year, the English lost Paris. After further failures, the English agreed to a truce with Charles VII in 1444.

In 1449-50 Charles VII invaded Normandy, with most places surrendering quickly.

The Battle of Formigny was fought between the English under Sir Thomas Kyriell, and a French army under Charles de Bourbon, count of Clermont. It was a significant French victory, despite the English holding a strong defensive position. The French force began the fight by discharging two light cannon. The English attacked and successfully captured the French guns, but instead of moving forward the English hesitated, only to face the Breton troops under Arthur de Richemont who joined Charles' soldiers.

The cannon were recaptured and the French armies surrounded the English, forcing them to attempt to fight in two directions. This split Kyriell's forces and the English were overwhelmed. Sir Thomas Kyriell was captured. There was little further English resistance - in August 1450, Cherbourg, the last English-held location in Normandy, fell.

Arms and Armour

People

Warfare underwent a gradual transition during the Hundred Years' War.

Medieval armies had been traditionally formed by using the feudal obligations of lords and tenants. During the 14th century however, England found that the feudal system was increasingly unable to supply the numbers of soldiers needed for sustained campaigns overseas. Instead, English kings turned to a system of paid contracts to raise men-at-arms and archers.

French kings also paid their troops but still relied on older feudal powers to raise armies. A career as a professional soldier was made possible because of the many wars.

Join the conversation