- Tower of London

- Torture and punishment

Warning: Content contains graphic descriptions of executions that may not be appropriate for younger children.

The Tower of London is famous for the many prisoners who met their end behind those cold, stone-grey walls. Ordinary people were usually hanged, but kings, queens, and other important people faced a different fate — beheading, by sword or, more often, by axe. Yet axes were common tools, used every day by builders, carpenters, and butchers. So, what makes an executioner’s axe different?

Warning: Content contains graphic descriptions of executions that may not be appropriate for younger children.

In February 1601, Robert Devereux, Earl of Essex, made his final walk to the scaffold at the Tower of London. A former favourite of the queen, Essex had returned to England after an unsuccessful military campaign in Ireland and quickly fell out of favour. He was accused of treason, arrested, and imprisoned at the Tower of London. After his trial, he was sentenced to death and executed facing the White Tower.

It is often said that the axe now on display at the Tower of London was the one used to dispatch Robert Devereux on that cold February day over four hundred years ago. But how can we be sure? Axes were commonly used in a variety of trades and crafts and normally designed for the task at hand. A butcher’s axe for example, with its short handle and broad blade, was ideally suited for cutting through flesh and bone. So, what makes an executioner’s axe?

Knowing the history of an axe head is the best way of discovering its use. This is known as provenance or understanding where an object came from. Axes used for executions are usually called heading axes and were made for one job - albeit a grim one. Although needing skill to be done well, cutting off heads was not thought of as a normal trade. The executioner or headsman was often selected for each occasion, but this does not mean they were skilled with the tool they were given. There are a number of well-known stories of executions that went horribly wrong. In 1541, Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, was supposedly chased around the execution block and the inexperienced headsman took 11 swings of the axe to get the job done.

A wretched and blundering youth... who literally hacked her (Margaret's) head and shoulders to pieces in the most pitiful manner.

Eustace Chapuys, Imperial Ambassador to England

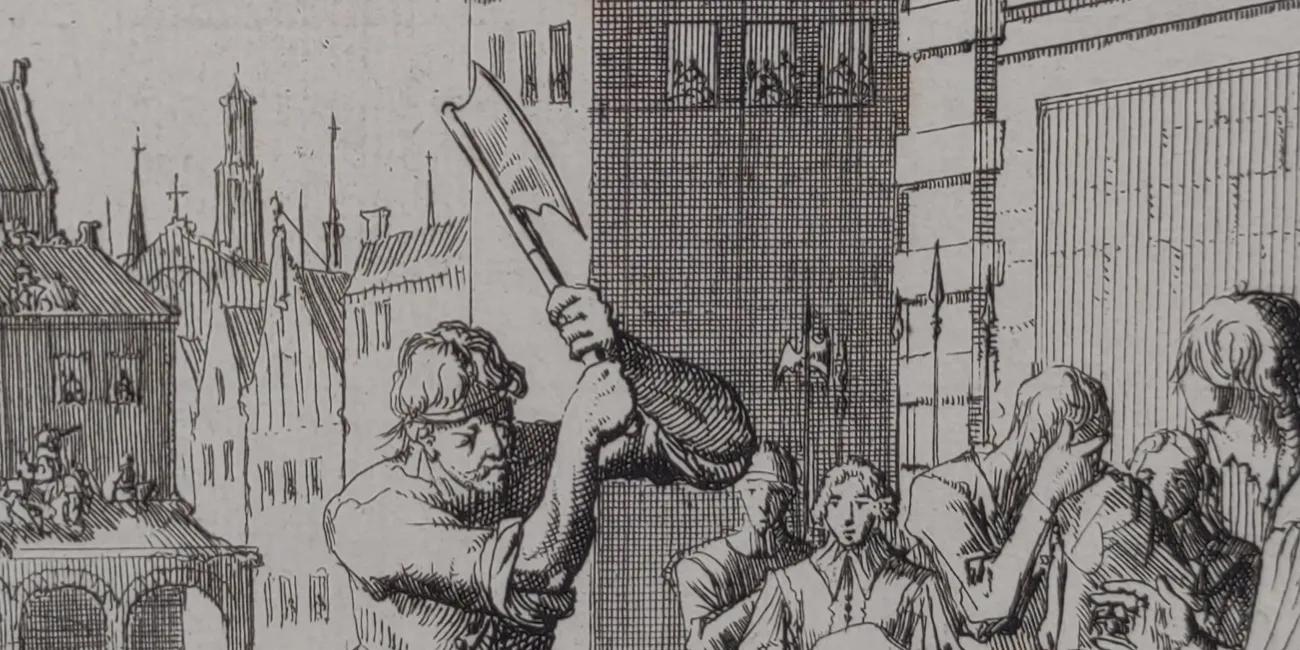

What can Margaret Pole's execution tell us about the type of axe used? As we see with Eustace Chapuys account, written descriptions often ignore the axe’s design when describing a victim’s final moments. Images of public executions are also not always reliable sources for identifying heading axes. Many depictions were made long after the execution or by those who had not seen the event.

The Tower of London’s heading axe is believed to be one of four that were stored there in the late-17th century. Unfortunately, there are no details about its use or who it may have been used on. But while we may never know if Robert Devereux’s head fell beneath its blade, the axe can tell us more about attitudes towards executions and class in England.

The method of execution often depended on your status in society. Common criminals could expect to be hanged. Beheading was normally preserved for only the most important people in society. Traitors, such as Guy Fawkes, may have been hanged, drawn, and quartered. This was an especially unpleasant form of execution where the victim was dragged through the streets before being hanged until half dead and finally dismembered.

It was primarily the English who favoured using axes for executions. Executioners in Europe normally preferred the sword. Instead of an English-style execution, Anne Boleyn, Henry VIII’s disgraced Queen asked for a swordsman and sword to be brought over from France for her execution in 1536.

Although we do not have much information on where the Tower of London's heading axe was used, we do know more about the block the axe is displayed with. For example, this was the same block used during the execution of Lord Lovat on Tower Hill in 1747. Simon Fraser, Lord Lovat, was a prominent Jacobite during the 1745 rebellion and was the last man to be beheaded at the Tower of London.

Following Lovat, beheading fell out of favour throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Laurence Shirley, 4th Earl Ferrers, was convicted of murder in 1760. He petitioned to be beheaded as a nobleman but was denied and instead was hanged at Tyburn, reportedly with a rope made of silk. The headsman, and his axe like the one on display at the Tower of London, was thankfully never again needed by the state. It remains a powerful symbol of the connection between power and punishment.

Join the conversation