How Fighting Helped Kings Keep the Peace

The Field of Cloth of Gold, or The King’s Triumph as it was sometimes known, was a diplomatic summit held between England and France in the summer of 1520, during the reign of Henry VIII. Sited near Calais and named after the spectacle created by its lavish fabric tents, this temporary encampment brought together two kings and a huge number of nobles, knights and servants. In this period, keeping the peace between nations was an energetic affair. The event involved competitive power dressing, hand-to-hand combat and giving a king a black eye.

Scot Hurst, Assistant Curator of Arms and Armour at the Royal Armouries, talks about this crucial royal get-together and the objects that help tell its story – including a suit of armour that prompted a phone call from NASA.

12 minute read

Had an event like this happened before?

Oh yes, throughout history. Several happened during The Hundred Years’ War [a series of armed conflicts between England and France in the 14th and 15th century] – there were some periods of peace in that time! And these meetings continued to be the done thing throughout Europe. Whenever you had a diplomatic event, inevitably lots of knights were in the same place at the same time, so it was a good opportunity for them to indulge in their favourite sports. Everyone let off some steam and aggression – they were executing what was essentially a proxy war, so it was a chance to flex muscles and rattle sabres! If your knights performed especially well in a joust, then that’s them saying to the other nation, ‘These guys are really good; we conduct our business very aggressively, so just watch yourselves.’ As curators we use the phrase ‘aggressive diplomacy’.

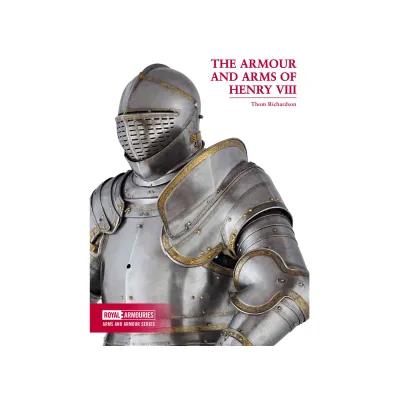

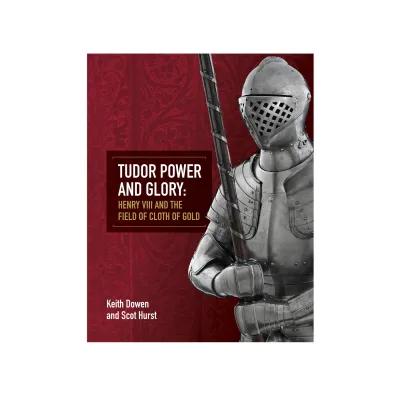

What object best represents the tournament?

The tonlet armour [‘tonlet’ means a long armoured skirt] – it’s a fascinating object. Its very existence is the result of the intense negotiations, the policy and the diplomacy of that time, and to the central role the tournament played in all those things. If you had to put one thing on a poster for the event, and Renaissance politics and diplomacy in general, that armour is a fantastic choice. It doesn’t conform to a pop-culture image of knightly armour, though. The skirted element demonstrates the use of civilian fashion, of textile fashion translating across into armour. Competitors wanted to go out onto the tournament field looking their best and looking fashionable, and that’s what the tonlet was about. It also offered practical protection for the upper legs and was a development of earlier battlefield armour design.

Why did knights wear textiles over their armour?

Looking at what’s in museums today, you get this very grey impression of how things would have looked. But events like The Field of Cloth of Gold would actually have been an absolute riot of colour. Personal heraldry and personal colours would have been very important. [Edward] Hall’s Chronicle describes fantastic colours being used, and we know that throughout each day and each event, there would be set themes and the costumes would have reflected those stories. It was a bit of theatre really, and costume is an essential part of any theatrical production. It was all about being seen, being noticed. In the group events, particularly, you would want to stand out. The bigger and more extravagant and more noticeable your costume was, the better. More was more!

Was object decoration meant to signify anything specific?

For Henry, England had been on the periphery of Europe politically, and we were seen as a backwater nation. These objects were all about demonstrating the wealth, the magnificence and the military might of England and Henry himself. He wanted to portray England as a progressive, forward-thinking state. He also wanted to portray himself as progressive, well-educated, philosophical and strong both politically and physically – a Renaissance prince. The decoration is very much an outward expression of his ambitions. Francis, on the other hand, even though he was younger than Henry, was already militarily very successful in Europe and had had a string of crucial military victories. He was also renowned as a patron of the arts and of philosophy. There’s a story that Leonardo da Vinci actually died in Francis’ arms, so he had a very good relationship with a lot of key European Renaissance figures. And you could say that to some extent Henry was trying to emulate that. Francis was in a sense leading the way and didn’t need to try as hard.

How many women attended the event?

Thousands of people went, including lots of women, but we don’t know the exact number. We can get a decent idea though, because it was specified exactly which nobles would go – and whether they were in the King’s party or Queen Katherine’s party. There’s only one surviving English invitation to the event, but it’s quite specific as to who you should bring with you and who you were accompanying. It’s highly likely that the lords and other nobles would have brought their wives with them. And there would be ladies-in-waiting accompanying the two queens. Women would have attended banquets and masquerades, and also been spectators. The two queens would have worn extravagant gowns; they would have been as impressive as the kings would have been. They’re representing their kings as well as their countries, so it was important to be tied into this idea of visual spectacle and magnificence. There were probably female staff at the tournament as well, working in the kitchens.

If you could go back in time, what would you ask the maker of your favourite object from the event?

Where do you even begin with a piece like Henry’s all-enclosing foot combat armour?! I think it’s a technical masterpiece. There’s a long-running story that this suit of armour inspired some of the space suits in the ‘60s. Apparently NASA did get in touch with the Tower [of London] to discuss it, but they didn’t actually come and study it. They wanted to understand how it totally encloses the body but you still get that full range of motion. How do you even begin designing something like that? Phenomenal! These are not modern saws and power tools; it’s men with hand tools. I would definitely ask the maker how daunting was it to start that project, and where did they begin?

Did anyone get killed at The Field of Cloth of Gold?

No people died. But there are anecdotes about injuries. Henry hit someone so hard jousting one day that he ripped the other man’s pauldron [the shoulder element of the armour] off. Francis received a black eye, which caused a bit of a panic. I may be wrong on this, but I do recall reading that some horses were killed during an accident in the joust. There was apparently a very high wind for a couple of days, which caused problems. And in what we call the lists, which is the area where the joust is run, Henry specifically requested no counter tilts to be used - that’s basically a funnel that guides the horses in towards the rail. We’re not sure why he said this and so the horses were prone to swerving around a bit. If I was to speculate, I'd say it would be to give him the opportunity to demonstrate his phenomenal skill in the saddle. In general, though, they were very careful rules-wise to avoid injury. If a rider did hit below the waist or below the barrier, he would be flat-out excluded from the event. But inevitably there were accidents – things happen.

Which object best shows how original finishes or gilding can change over time?

There are some faint traces of gilding within some of the etchings on the helmet of the tonlet armour. On his all-enclosing foot armour, though, the finish on the metal that you see now is not the original finish because it would have been left ‘black from the hammer’. The current finish is basically generations of bored wardens at the Tower of London polishing it up when they had nothing to do! With the foot combat armour, when you look under the overlapping plates, you can see where they’ve not been able to get at it to polish it – it’s still black from the initial smithing. So there are traces of different decorative finishes that we can pick out.

In an emergency, which object from the tournament would you race to save?

I really like the set of armourer’s tools. I think they are some of my favourite things in the entire collection because they are so relatable. The design of the tools hasn’t changed. There are various shears, hammers, chisels – you know, exactly the same stuff that you could find in Homebase or B&Q today. It was 500 years ago these guys were using those same things. I think that’s amazing. Plus, the tools are smaller and more manageable than armour, so in the rush of an emergency they’d be easier to grab!

How did news of the tournament get out into the world?

Books and pamphlets. There were chronicles written by people like Edward Hall. He was the official chronicler and historian of London and, I suppose, the Tudor dynasty. He was at The Field of Cloth of Gold noting everything down. And diaries were very important. It’s likely that word would have spread quite fast – purely because, it’s estimated, 90 per cent of the English nobility went to France for this event! They basically emptied the elite out of England, so it wouldn’t have escaped the common people’s notice. Pamphlets were then sold after the event, plus there were heralds travelling around. There was no point having events like this if your subjects were ignorant to it. It’s not just about impressing the important folk, it’s also about stamping Henry’s authority, his desired image, his magnificence, his status on the ordinary people – because ultimately, they’re the ones who make or break you.

Which object is it worth having a closer look at?

The skirt of Henry’s tonlet armour. Traditionally that piece has had a bad narrative surrounding it because everyone thinks ‘Oh, it was made in three months; it was cobbled together from pre-existing parts.’ There’s actually a mistake in the decoration on the back of it. But when you get up close and appreciate the actual workmanship, the artistic accomplishment that’s gone into it, I think that makes it worth having a really good look. And you can see that different people have worked on different things – there’s a slight difference in the execution of the etching.

If you had attended the event, would you have rather been a competitor, a tent maker or a cook?

A competitor! Absolutely – you’d want to be the centre of attention! These are the celebrities of the day; these are your pop stars. You ride out there and everyone starts cheering for you and chanting. The atmosphere would be very much like in the film The Knight’s Tale.

If you could give one tournament object a voice, which would it be?

The Horned Helmet. Its history is very, very interesting: the fact it was a diplomatic gift armour from Maximilian I* to Henry VIII. It’s a parade armour – so it would have only been worn in a parade, a procession. In the lead up to The Field of Cloth of Gold everyone was trying to court Henry, to try and establish their own power in Europe. And likewise Henry wants them to court him because he wants his own foot in the door in Europe - Maximilian is trying to impress him, Francis, the French King, is trying to impress him. We also think the Horned Helmet has been tinkered with within its working life: the ram’s horns and the spectacles were later additions. There’s also an interesting story that it belonged to Henry VIII’s jester. Then there’s the fact that the rest of this suit of gift armour subsequently went missing – which may or may not have been the result of the English Civil War, we’re not sure. I think the stories this helmet could tell in the lead up to the event, and afterwards, would be fascinating.

* Maximilian I was the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, a role that made him the head of an empire stretching across Western, Central and Southern Europe, and which, at the time of The Field of Cloth of Gold, was equivalent in political importance to the Catholic church.

What object would you like to add to the Royal Armouries Field of Cloth of Gold collection?

They would never, never let us have it (!), but the Met [The Metropolitan Museum of Art] in New York has a helmet called the Capel Helm, which belonged to Sir Giles Capel. He was at The Field of Cloth of Gold and accompanied Henry during the first meeting of the kings, so he was within Henry’s inner circle. He competed on Henry’s team and took part in most of the events, so basically he’s a central character.

What else is there to know about the tournament?

There’s so much! What were lots of women really doing there?! We know that carpenters and blacksmiths were present but their stories get lost in the mix. The chroniclers and the diarists that went were interested in what the kings and the knights were doing and not the day-to-day running of the event. We have no real idea of how it worked. Who was bringing the food and from where to where? As for the layout, we only have one painting and it’s very stylised and the locations aren’t in context. There’s loads we’d still like to find out, but the sources just don’t exist. So much time has been spent on The Field of Cloth of Gold already, it’s hard to know what future research will uncover.

If you could take one of these objects home for the weekend, which would you choose and what would you do with it?

The Horned Helmet. It’s certainly not a practical piece of battlefield armour, it’s all about show and extravagance. It’s an amazing object – so visually striking and intriguing. It’s an object purely for putting on, getting on a horse and riding down the street looking great. You can show that helmet to anyone and it will start a conversation, whether or not they have a pre-existing interest in arms and armour or the Renaissance. I’d take it on a night out – absolutely! You’d probably need to use a straw to get at your beer, though.

Join the conversation