History of the Tower Armouries

The Royal Armouries can trace its history back 700 years in the Tower of London. In July 1323, John Fleet was appointed as 'keeper of the part of the king's wardrobe in the Tower of London'.

This marked a key development of the Privy Wardrobe, and the Tower of London into a place of manufacture and storage of arms, armour, and artillery.

Origins

The origins of the Armouries can be traced back to the working armoury of the medieval kings of England. Although the Tower of London did not become the main royal and national arsenal until the 14th century, the armoury had occupied buildings within the Tower for making and storing arms, armour and military equipment for as long as the Tower itself has been in existence.

An important chapter in the development of the Armouries occurred in the mid-15th century, with the Office of Ordnance and Office of Armoury replacing the Privy Wardrobe. These offices were responsible for procuring and issuing a wide variety of military equipment. The Armoury concentrated on armour and edged weapons; the Ordnance concentrated on cannon, handguns and the more traditional bow and arrow.

The first visitors

One of the earliest recorded visitors to the Tower Armouries was in 1498, when entry was only by special permission.

By the end of the 16th century, some of the early visitors to the Tower began to record their impressions of the Armoury. Jacob Rathgar, secretary of Frederick, Duke of Württemburg, described what they were shown in 1592. Despite the presence of many fine pieces of artillery, Rathgar felt the collection did not compare with those in his native Germany, ‘for they stand about in the greatest confusion and disorder’.

Paul Hentzner provided the first detailed description of the Armoury after a visit to London in 1598. He was shown many items belonging to Henry VIII, including a gilt suit of armour, and several historic cannon; among them two wooden, dummy cannons used to deceive the French at the siege of Boulogne in 1544.

The following year Joseph Platter, a Swiss traveller from Basle, visited the Tower and again paid attention to the personal armoury of Henry VIII, which was located in the White Tower. Interestingly, he referred to the cost of viewing the Armoury - he made payments at four points during his visit ‘to a servant appointed to receive the same’.

Rathgar’s complaint in 1592 about the disorderly appearance of the Armoury, repeated by the Duke of Stettin-Pomerania a decade later, suggests that little attention was paid to presentation in the late 16th and early 17th centuries.

New displays

This situation was to change immediately after the restoration of King Charles II in 1660, when two permanent public displays were set up and the paying public was permitted entry to marvel at new displays set up to celebrate the power and splendour of English monarchy.

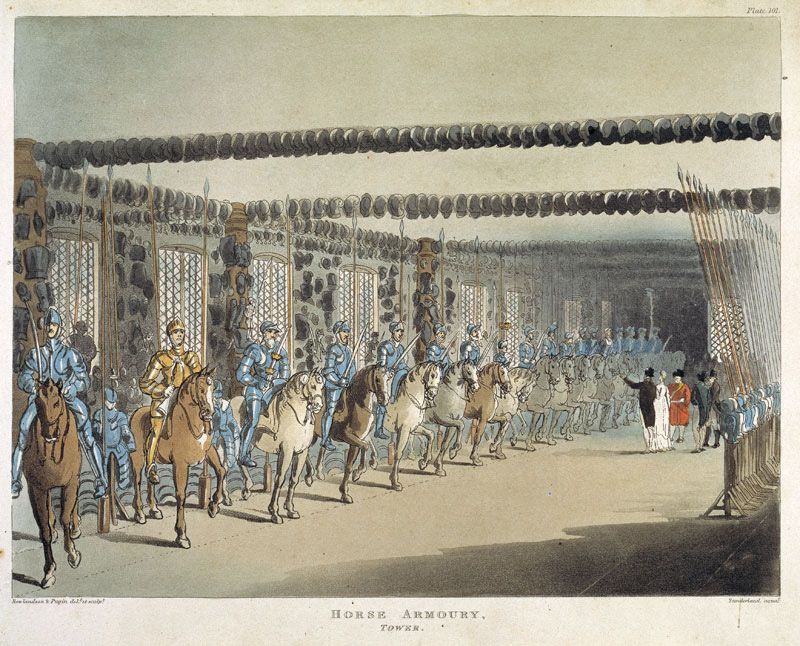

Later these displays became known as the 'Line of Kings' and the 'Spanish Armoury'. The former, as the name suggests, was a row of figures representing the kings of England. The line was first recorded in the Tower in an inventory dated October 1660, and it is possible that the display was assembled to mark Charles II’s visit to the Tower of London in August that year, after his many years in exile. The figures appeared on life-sized wooden horses, wearing what was said to be their personal armour.

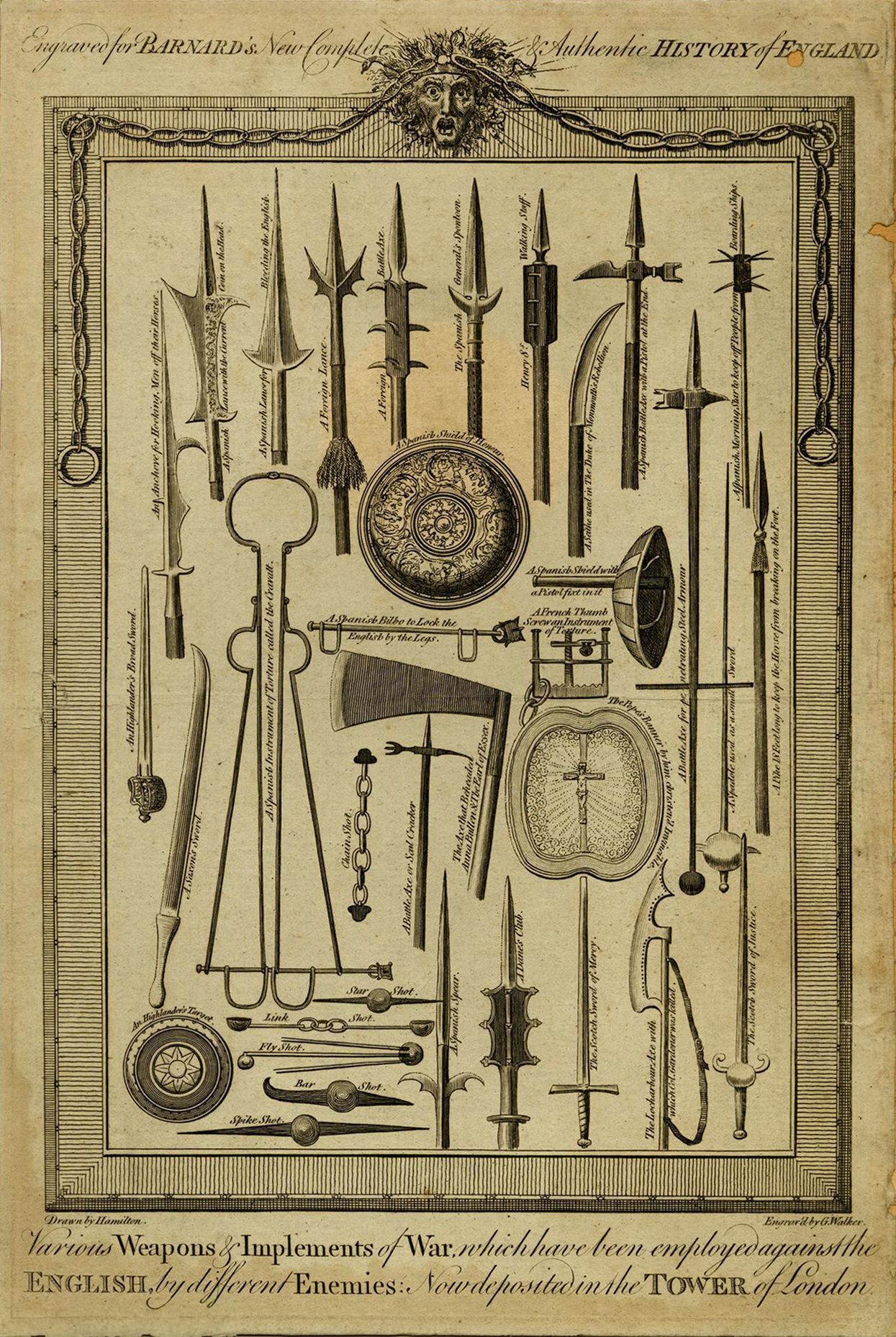

The Spanish Armoury was a collection of fearsome-looking weapons, displayed alongside instruments of torture, claimed to have been taken from the Spanish Armada in 1588. However, few, if any, of the objects had Spanish connections.

The Office of Ordnance

Developments in the art of war resulted in the Ordnance becoming the more important of the two organisations, and in 1670 the equipment and functions of the Office of Armoury passed to it.

Towards the end of the 17th century, the Office of Ordnance added two new displays of arms and armour to the visitor attractions at the Tower. These were housed in one of the largest and most prestigious buildings ever to be seen at the Tower – the Grand Storehouse. Built on the high ground immediately north of the White Tower, it was completed in 1692.

The third, fantastic, display was installed on the first floor in 1696. Under the supervision of John Harris of Eaton, tens of thousands of small arms, and a mass of elaborate wooden sculptures, were used to create such diverse installations as the ‘Witch of Endor’, the ‘Back Bones of a Whale’, a huge organ, and a seven-headed monster.

On the ground floor, stood the great guns of the artillery train. As time went by, the room increasingly took on the appearance of a museum of military power, in which cannon and other trophies captured from battlefields around the world were displayed. The displays also included items of curiosity and historic interest. Perhaps one of the most infamous was the Tower ‘Rack to extort Confession’, which had only been decommissioned by 1675.

Throughout the 18th and into the early 19th century, the Ordnance Office continued to review and revise its four displays at the Tower.

In 1825, the decision was taken to re-locate the Line of Kings into a new building against the south side of the White Tower. The New Horse Armoury was architecturally significant as it represented the first purpose-built gallery at the Tower. With the move, the notable antiquarian Dr Samuel Meyerick reorganised and reinterpreted the exhibits along more scholarly lines.

Moreover, the Ordnance Office was allowed to use ticket revenue to purchase more objects for the collection. The first decisive steps had been taken to transform the Tower armouries into a modern museum.

Modernisation

Early in the 19th century, the nature and purpose of the displays began to change. They were gradually altered from exhibitions of curiosities to historically ‘accurate’ and logically organised displays, designed to educate the visitor by presenting historic objects including arms and armour.

In 1838 the cost of visiting the Tower Armouries was cut from three shillings to one shilling and lowered again the following year to six pence. As a result, visitor numbers rose from 10,500 in 1837 to 80,000 in 1839.

On the evening of 30 October 1841 the Grand Storehouse was engulfed by a terrible fire destroying most of the displays within.

During 1855 the Office of Ordnance was dissolved by Act of Parliament and the armouries collections transferred the War Office.

The shortage of display space only began to be eased with the demolition of the Horse Armoury in 1882 and the transfer of much of the collection into the upper floors of the White Tower.

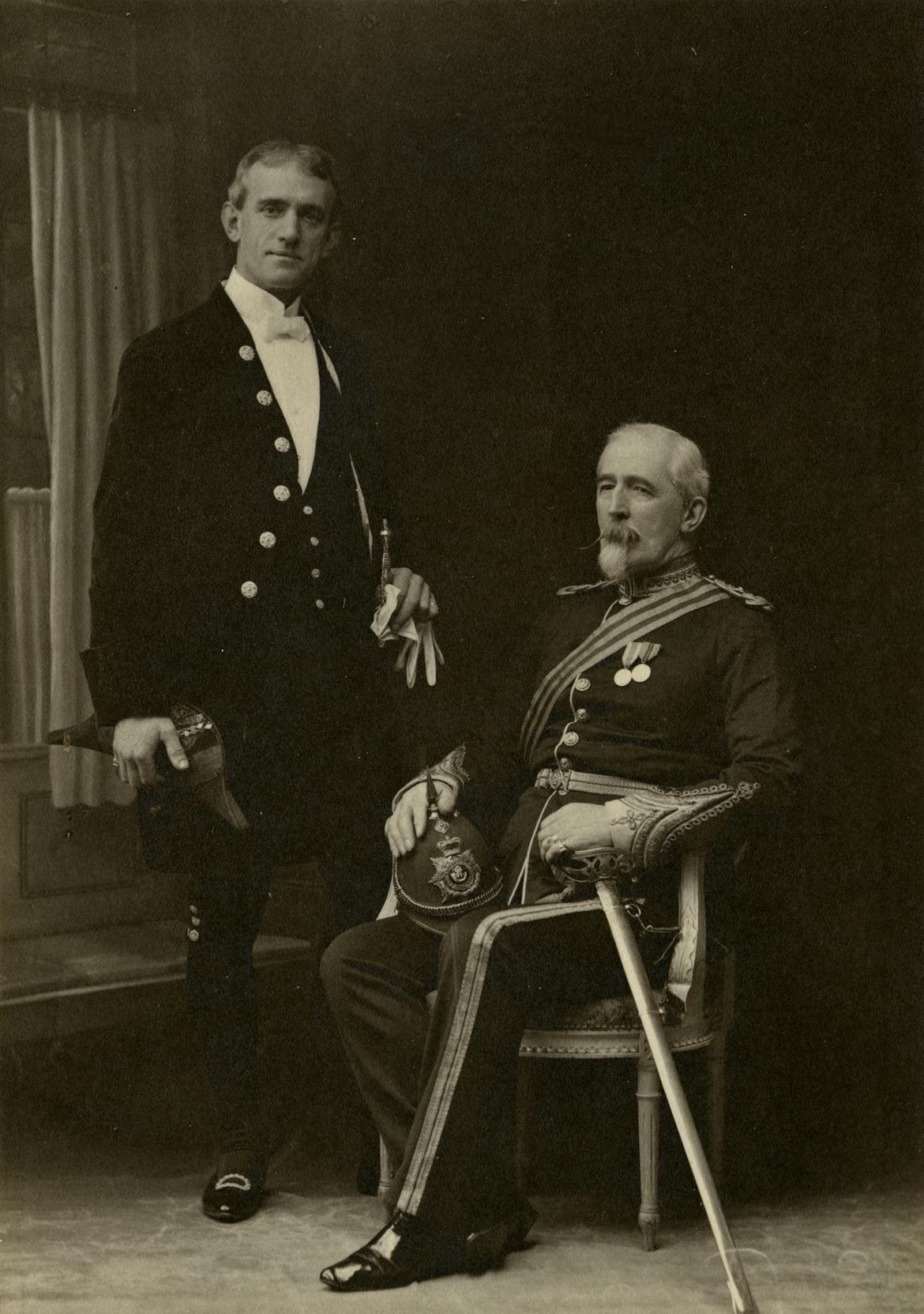

The presentation of these displays and the care and identification of the individual objects was greatly improved after the appointment of the first curator, Lord Dillon, as Keeper of the Armoury in 1895. Under the supervision of his successor, Charles ffoulkes, the displays expanded to occupy the remaining floors of the White Tower by 1916.

Before then responsibility of the Tower Armouries was passed to the Office of Works in 1904 and subsequently through its successors, the Ministry of Public Buildings and Works and the Department of the Environment, until the passing of the National Heritage Act in 1983. Today the museum is funded by annual grant-in-aid from the Government.